Identifying Birds:

Where? When? What? leads to Who? and often Why?

Each of the sections below details strategies for identifying birds.

When you're ready for more, checkout The Cornell Lab's excellent Bird Identification Tutorial called Build Your Bird ID Skills.

A Field Guide is the first step in reducing the number of species one might need to consider in trying to identify an unfamiliar bird.

Whether a Field Guide is a printed book or an online resource, it is always designed to serve a particular geographical area.

There are Field Guides for individual continents or for individual countries or for individual states within a country.

Once you have an appropriate Field Guide, the next step in reducing the number of species to consider in an identification is consulting the range maps.

Each species has its own unique map. Shaded areas on the map show you where that particular species occurs:

If you use The Cornell Lab's bird identification App, Merlin, the first question it asks is "Where did you see the bird?"

It is unusual to see an "eastern species" in New Mexico. However, "out-of-range" birds (a.k.a Vagrants) do sometimes show up. In fact, for most bird-watchers, such sightings are special events!

However, there may be other explanations.

The plumages of birds vary from female to male, from juvenile to adult and from season to season. So what might seem like a "new" bird may simply be a plumage you've not seen before! When considering a low-probability species (out-of-range), it is useful to first carefully eliminate the variants of higher-probability species (in-range).

For novice bird-watchers this may mean looking through your field guide page by page until you work out the identification! (Yikes!) As you begin to learn the family groupings of birds and their shared characteristics the whole process becomes easier.

Perhaps you have some other questions now, like

- "Why are there different colors on the map?"

- or

- "What about different habitats?"

- or

- "What about different elevations?"

In addition to showing location, Range Maps encode time.

One of the most engaging aspects of birds is the reality that they have wings. They can fly and they move around the landscape. We are used to seeing birds fly across a road or a field, or even across most of the sky. But sometimes, that bird we see flying has just finished a 10-mile flight from tall pines in the mountains downslope to where we are in the valley. When you see that first Turkey Vulture in Spring, it may have just finished a two-month flight from Venezuela where it spent the winter.

Birds migrate both short and long distances and the use of different colors on a range map can reveal the yearly migrations of a species.

Here are three typical Range Maps:

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to EnlargeUsing the "key" to the map, we see that this species is listed as a Permanent Resident in the map area shaded purple.

This bird can be found in that area during all seasons.

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to EnlargeThis species is a migrant.

- In the Summer, it is found on its Breeding Ground (Red)

- In the Winter, it is found on its Wintering Ground (Blue) in Southwestern Mexico

- Each Spring and Fall it will pass through the Yellow area on its migration between its Breeding and Wintering grounds.

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to EnlargeThis species is also a migrant.

- During the Winter, almost all Robins are in either the Purple or the Blue areas.

- In the Summer, the Blue areas are vacated and large numbers of Robins migrate north into the Red areas while large numbers remain in the Purple area.

- Note: The Robins we see breeding in the summer are not necessarily the same individuals we see in the winter months.

Range data provided by Infonatura/Natureserve. Ridgely, R. S., T. F. Alnutt, T. Brooks, D. K. McNicol, D. W. Mehlman, B. E. Young, and J. R. Zook. 2005 Digital Distribution Maps of the Birds of the Western Hemisphere, version 2.1 NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia, USA

Traditional Range Maps use solid colors to indicate the seasonal ranges of a species.

They are very useful and represent a great amount of very detailed work to develop.

The ranges are derived from an exhaustive search of the scientific literature and available field data from many, many sources.

As ranges and abundances of species change over the years, an update of a set of range maps for all the species of a region requires a substantial investment of time and energy.

The collection of Range Maps that exist in current editions and past editions of field guides represent a valuable historical record of the changes in species status. It is true that the underlying data exist in the scientific record, but the range maps provide a powerful visual summary of that data.

Now, consider the map below:

eBird Abundance Map for Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus):

Here is an eBird Abundance Map for the same species.

There are thousands of bird-watchers across the hemisphere entering their bird sightings into the eBird database every day.

Since the Location, Date and Species of every sighting is stored in the database, a much more nuanced and detailed range map can be created.

Bird-watchers in Northern New Mexico know that the Rufous Hummingbird does not show up each year until the first week of July. This range map demonstrates why.

Here, the Spring migration (shown in green) and the Fall migration (shown in yellow) are shown separately.

In the Spring, moving north, the Rufous Hummingbird migrates primarily in coastal states. In the Fall, on the return trip south, the migration routes are much more widespread, reaching across the Great Basin and the Rocky Mountains.

The Rufous Hummingbird is one of the many species that utilize a circular migration pattern. Some patterns are Clockwise and some are Counter Clockwise.

Click here to access eBird Abundance Maps in eBird "Science/Status and Trends" (Opens in new Tab)

eBird Range Map for Rufous Hummingbird (Selasphorus rufus):

eBird also produces a more traditional range map.

Here is the eBird Range Map for the Rufous Hummingbird.

Here solid colors are used to depict the seasonal ranges like in a traditional range map.

You lose some detail in the solid areas compared to the eBird Abundance Map.

However, relative to a traditional map, you gain detail about areas where the bird does not occur.

This map also retains the very useful separation of the Spring (green) and Fall (yellow) migrations.

eBird range maps are available on the same page as the abundance maps:

Click here to access eBird Range Maps in eBird "Science/Status and Trends" (Opens in new Tab)

Range maps encode Geography and Time but not Habitat:

Consider this Range Map:

The color key on the map tells us this species is a permanent resident in the area shaded purple.

From the close-up it appears that the bird shows up across most of New Mexico.

But it turns out this map is for a bird called the American Dipper:

This bird is usually seen standing on rocks in mountain streams or disappearing into the stream to walk on the bottom in search of food. During the breeding season you may see one a few feet away from the stream, but no where else!

So: Range Maps encode geographic location, but not habitat! Most of the purple shaded area on the map is not mountain streams. If you want to see an American Dipper, you must go to a mountain stream.

Female:

Male:

Male:

The Red-winged Blackbird is an iconic bird for the Rio Fernando Wetlands.

The principal breeding areas for this species are marshes.

They breed at various altitudes and utilize both fresh and salt water marshes.

Outside of the breeding season, they appear in many habitats.

But if you want to see them during the breeding season, you will find them in marshes or similar wetland habitats.

FOOTNOTE...

Sometimes the name of a bird suggests its habitat. Here is a Juniper Titmouse sitting on top of a Juniper Tree:

The Juniper Titmouse is almost always seen in Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands.

You can invest as much time as you like searching high montain forests or vast grasslands, but you won't find this species unless you are in or near Pinyon-Juniper woodlands.

There are many ways to classify habitats. This listing is particular to the Rio Fernando Wetlands and the surrounding area. With experience you will learn which birds use which habitats. The "edges" between habitats are often very good places to find birds.

- Riparian: River, Beaver Dams, Wetlands, Willow Thickets, Cottonwoods

- Transition: Riparian to Irrigated Fields

- Irrigated Fields: Grasslands, Crops, Gardens, Hedgerows.

- Transition: Irrigated Fields to Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands (Acequias Often Present)

- Pinyon-Juniper Woodlands

- Mesa-top Grasslands or Sagebrush

- Pine Forests further upslope.

Range maps do not encode elevation. Here are three species whose range maps do not precisely indicate their occurrence and movements in Northern New Mexico.

These three species are present during the winter months at the RFW. During the Spring migration, some of them will move north, but some of them will move up into the nearby mountains for breeding. They will remain until the Fall.

You will not hear them singing during the winter. Only a dry "tick" from the Juncos and an insistent "ji-jit" from the Ruby-crowned Kinglet. The Hermit Thrush will likely remain silent.

If you want to hear these birds singing you can drive up to Amole Canyon in June. The Junco will be making its long trill. The Ruby-crowned Kinglet will be making its rolling-rollicking song that seems much bigger than that very small bird should be capable of making. The Hermit Thrush will be sounding its ethereal fluting notes. They will drift over from somewhere upslope, out of sight.

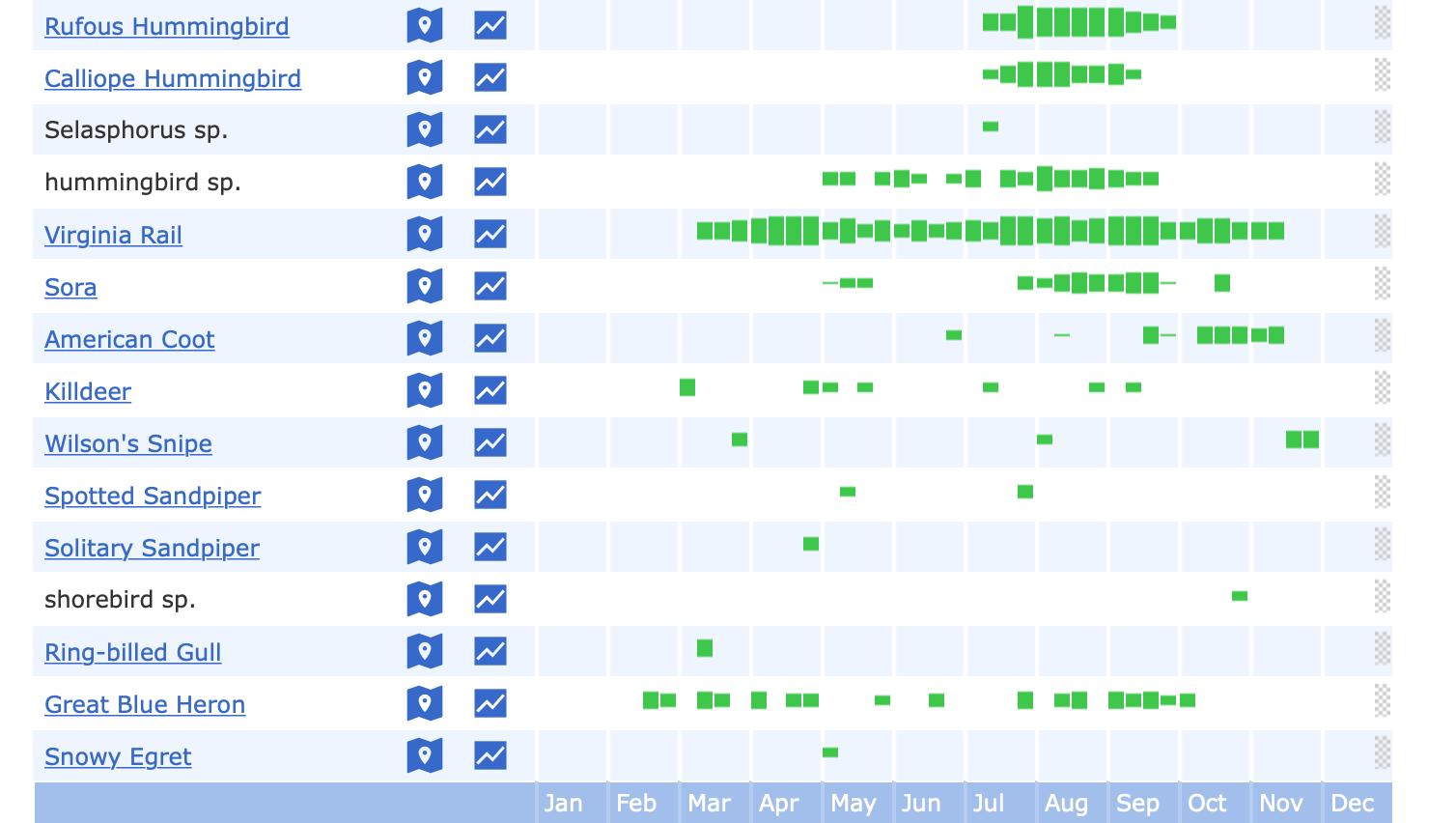

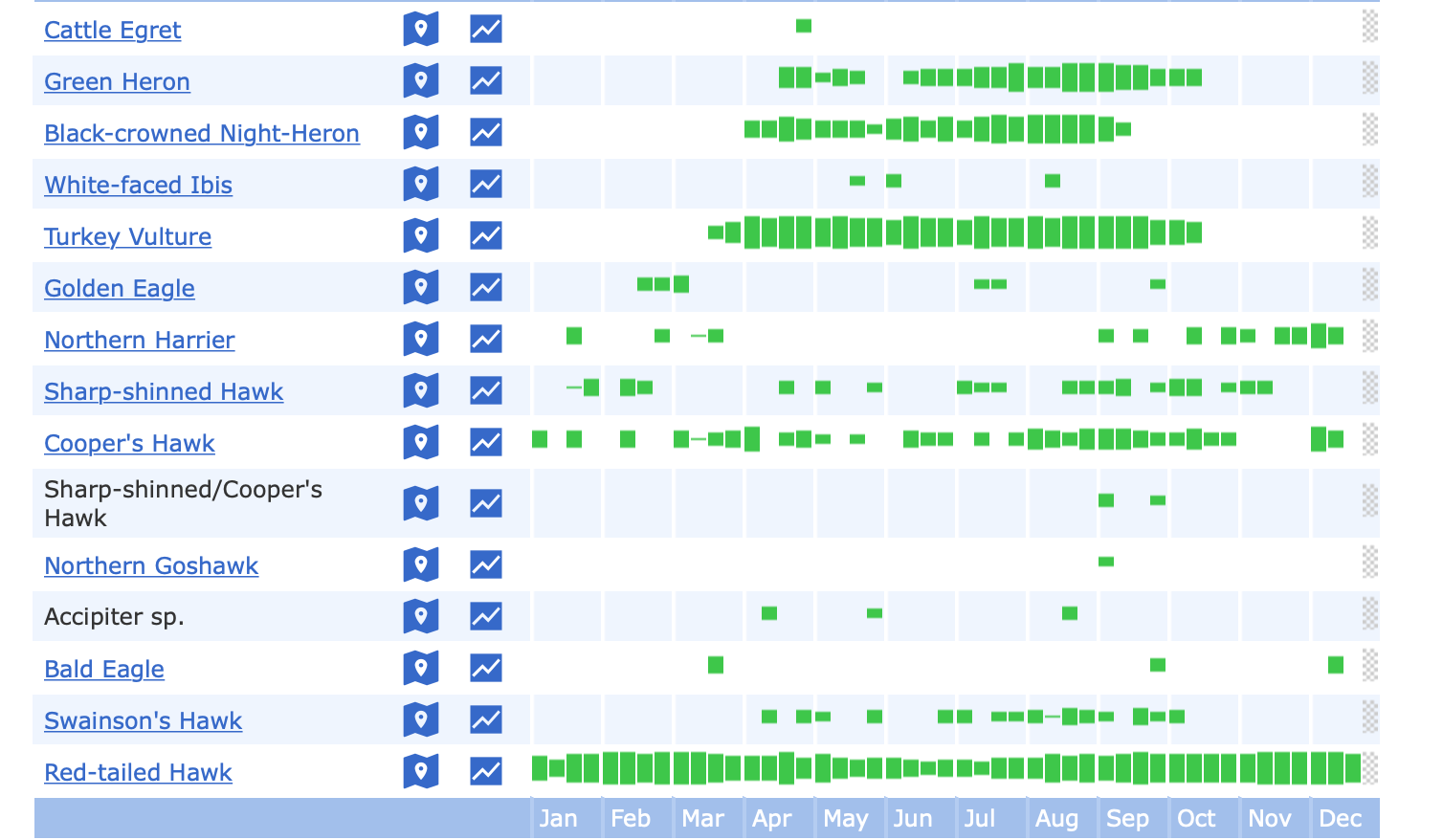

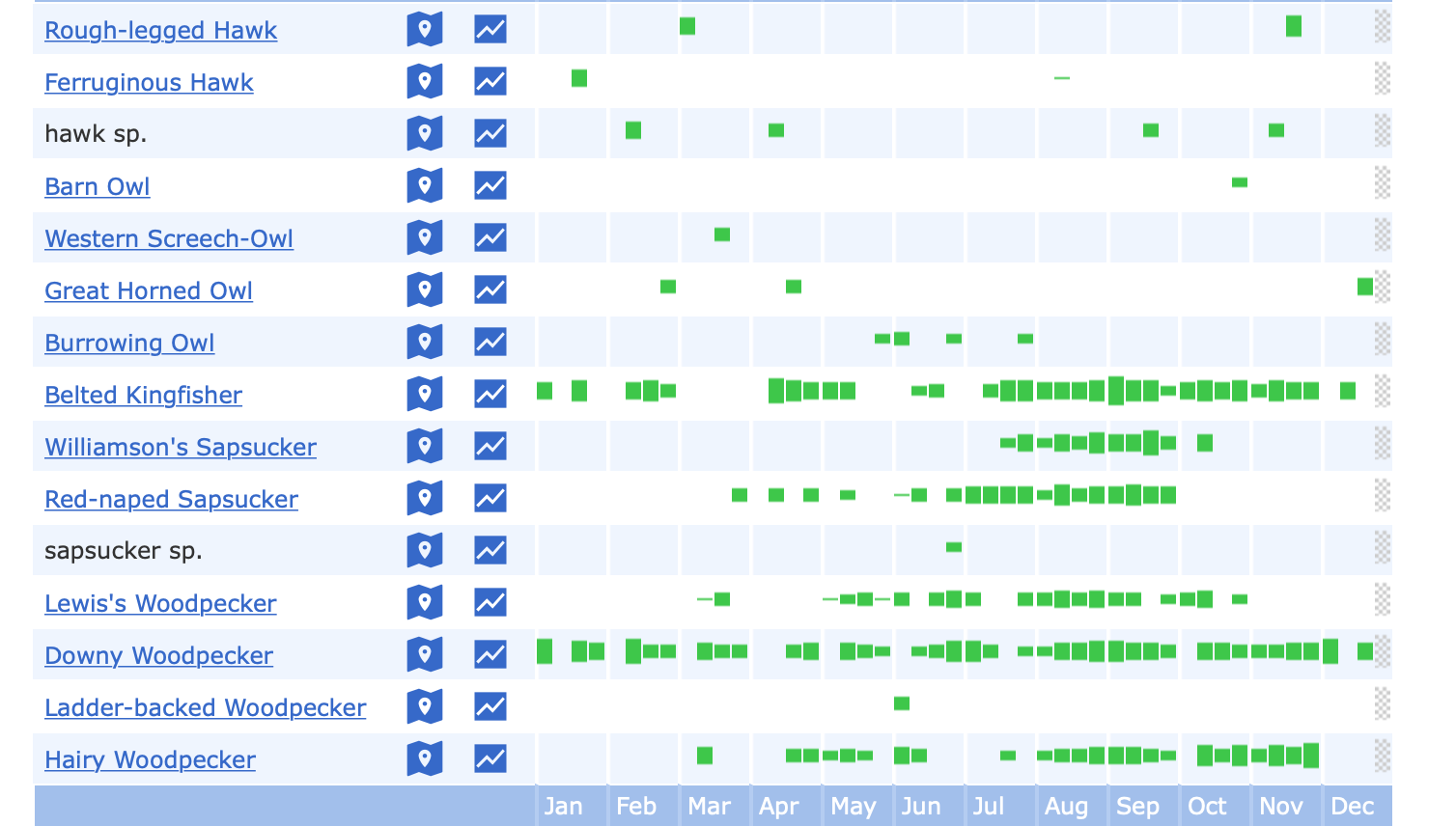

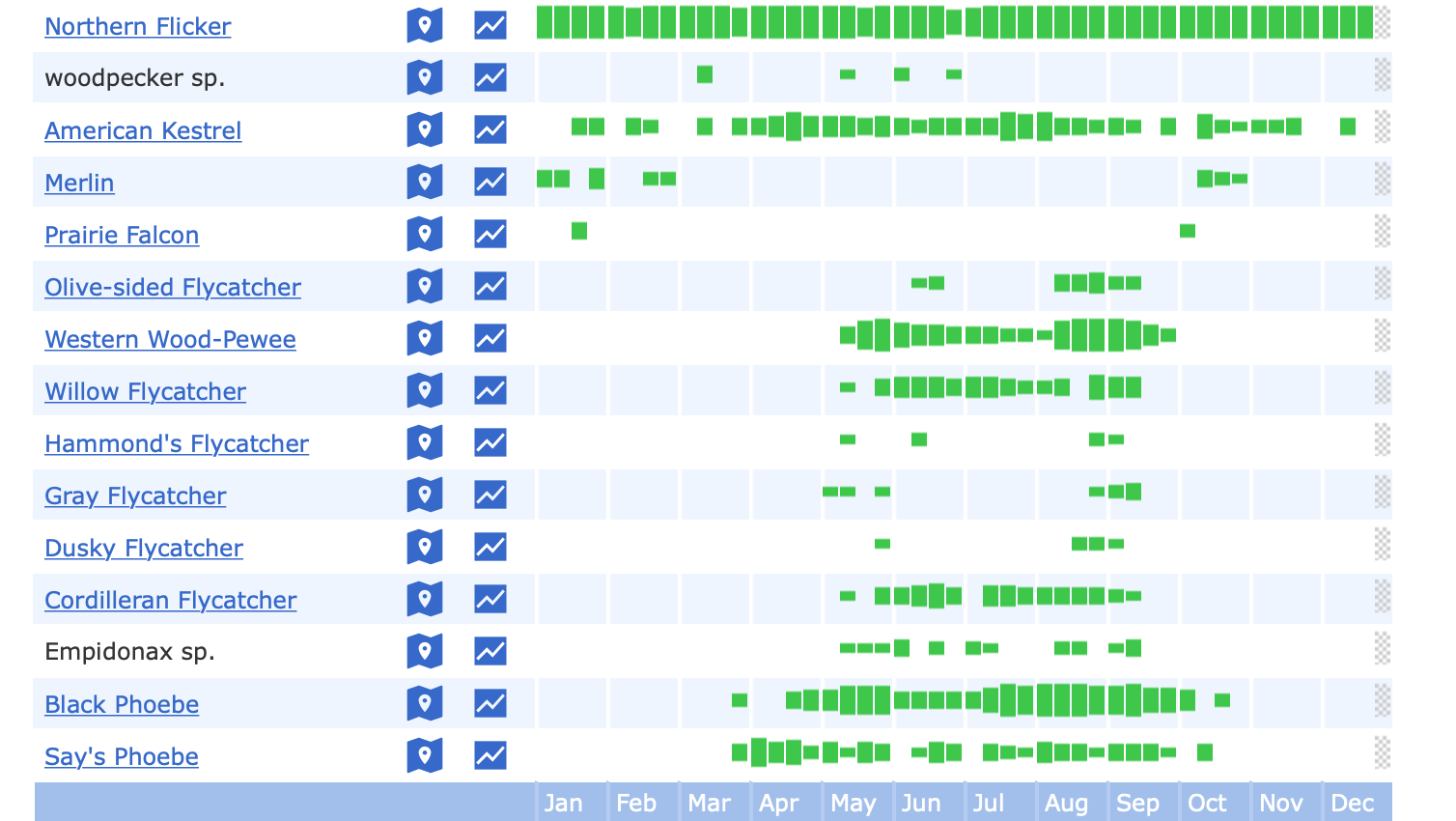

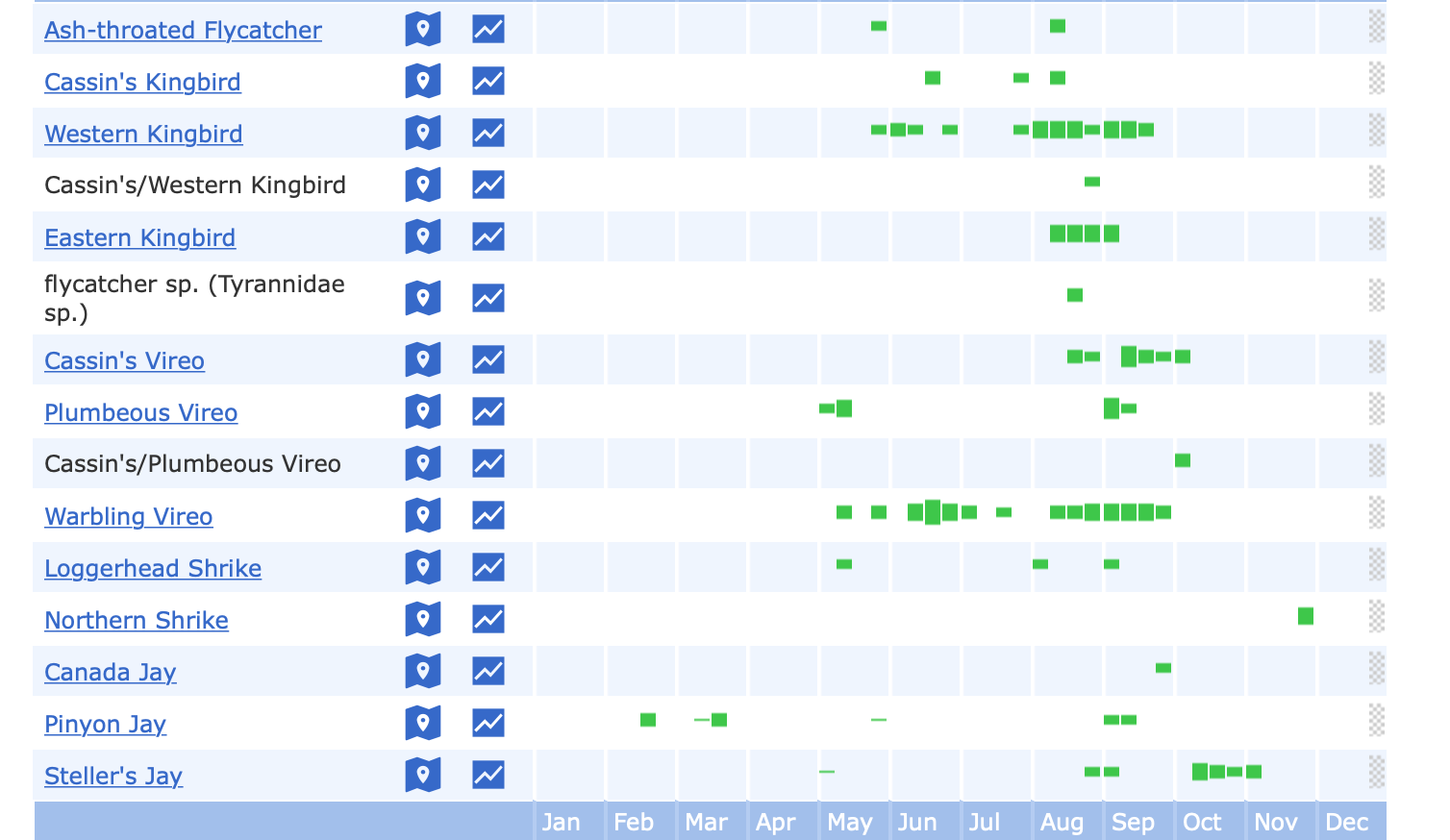

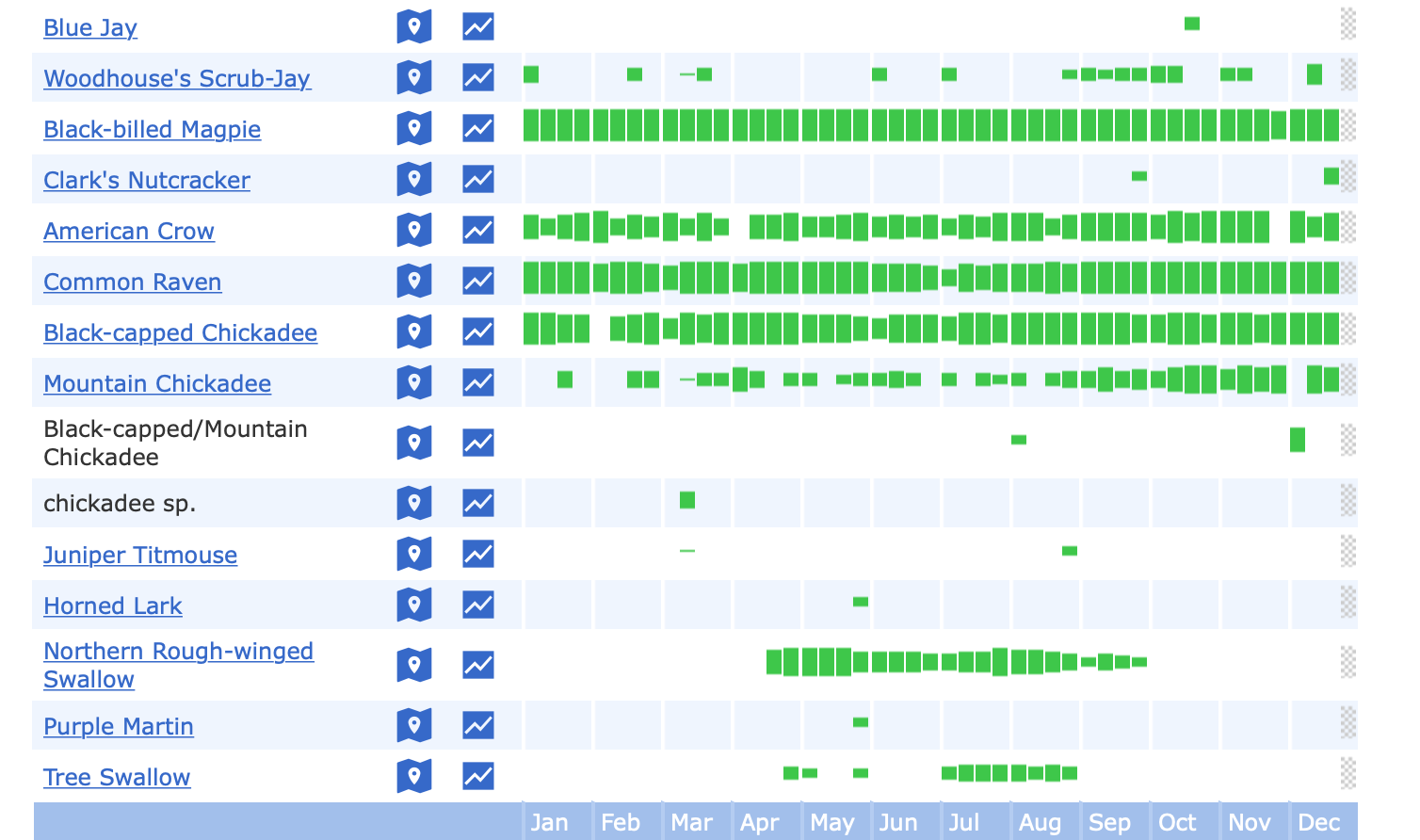

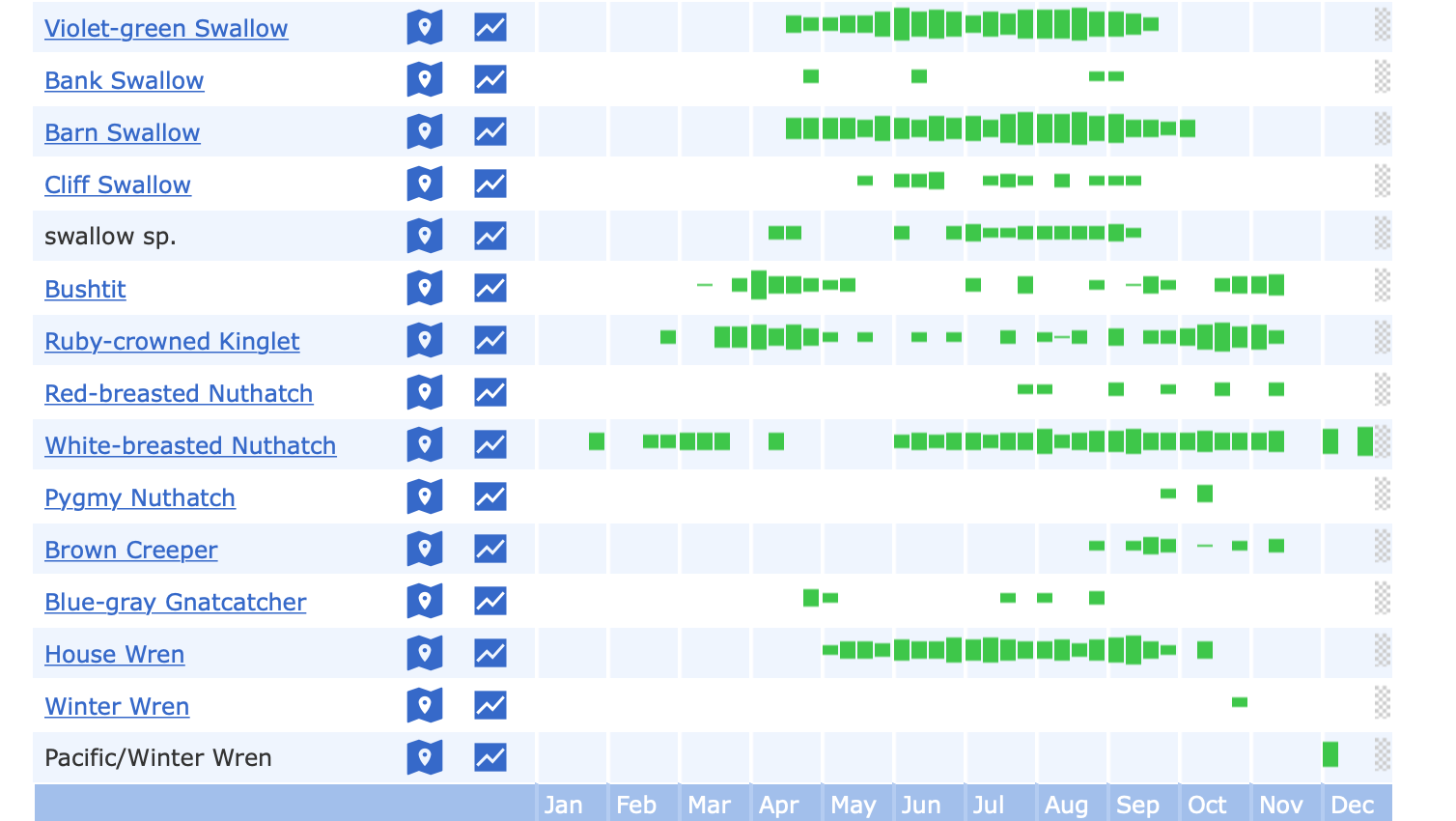

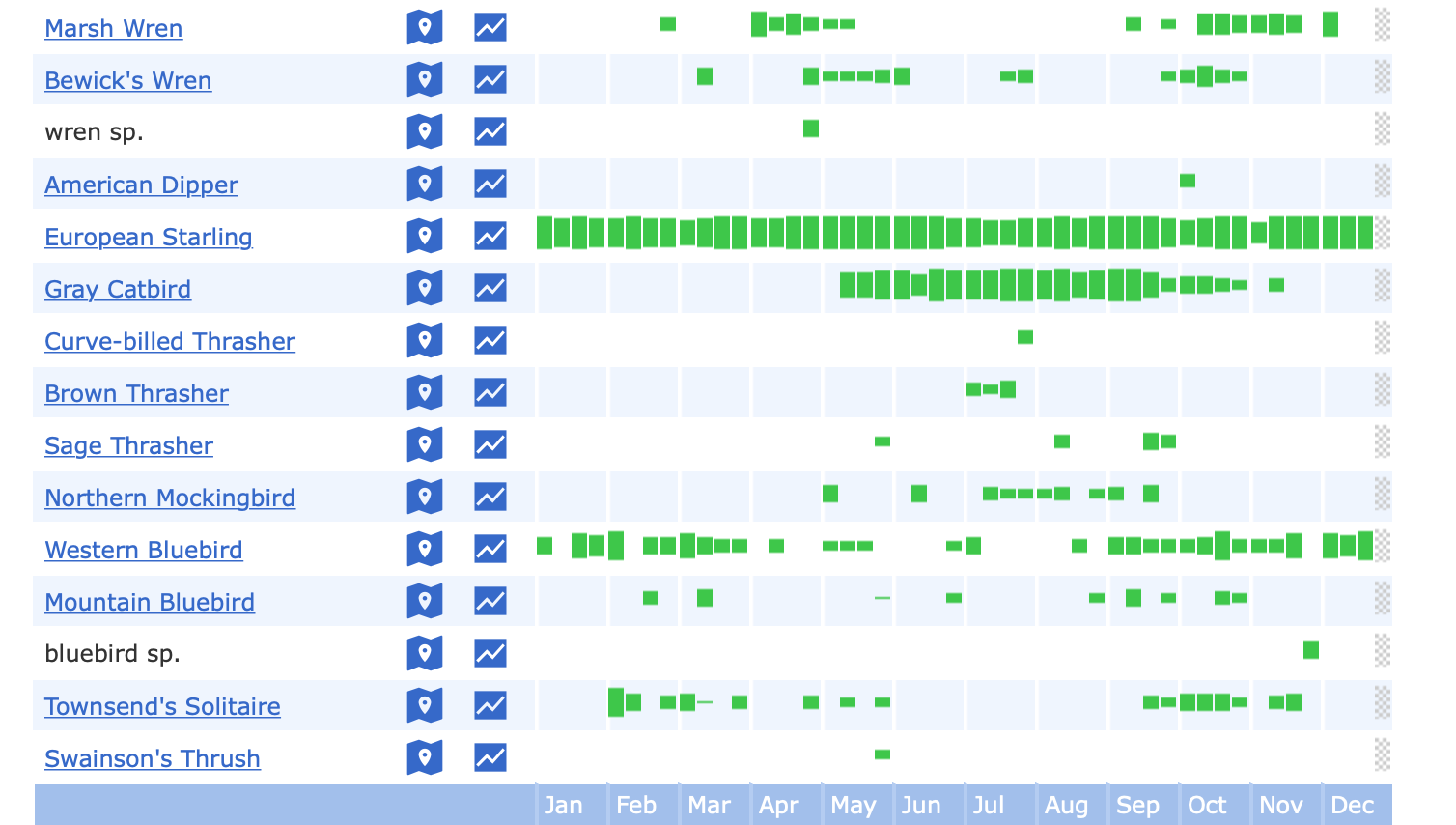

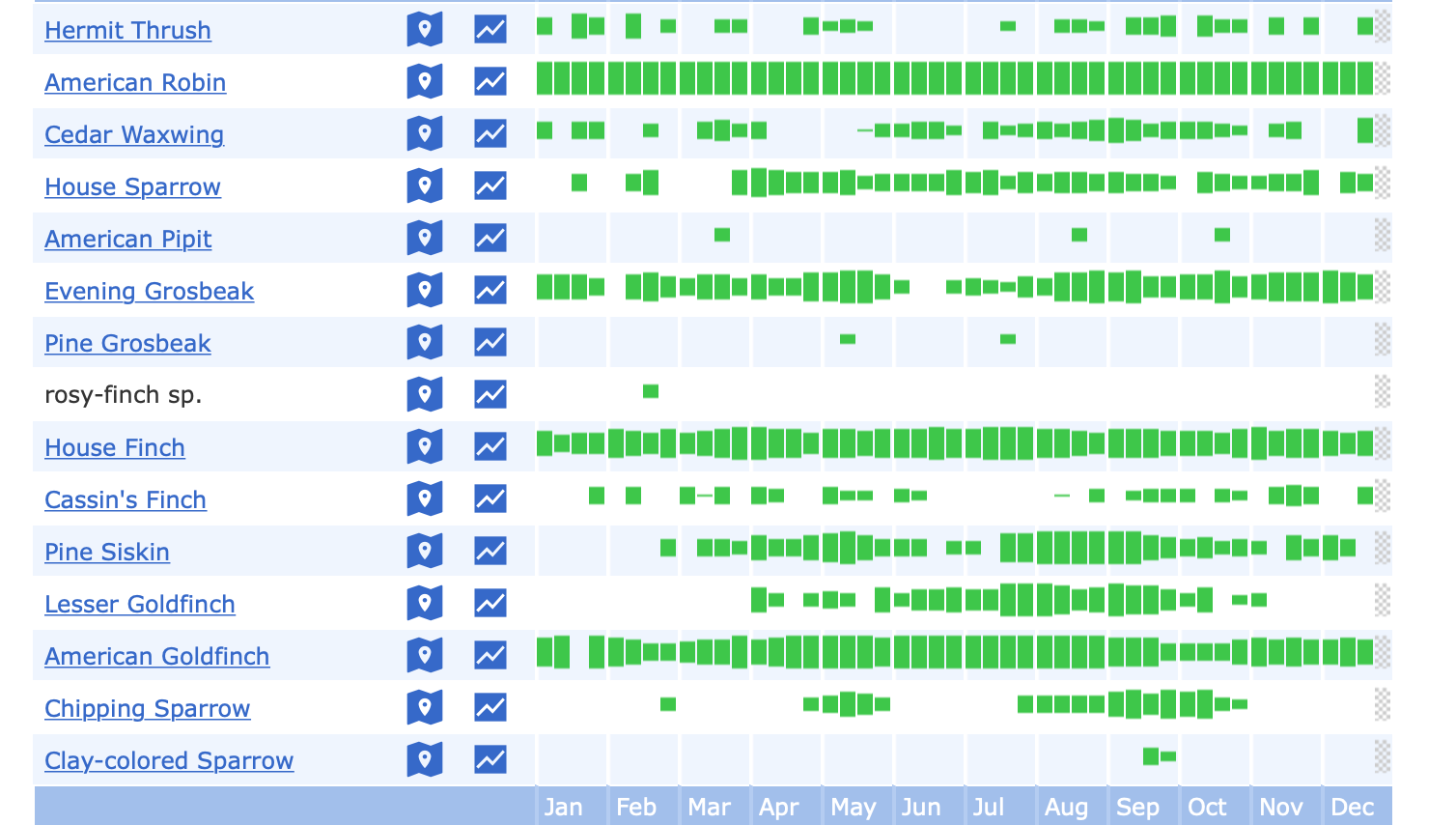

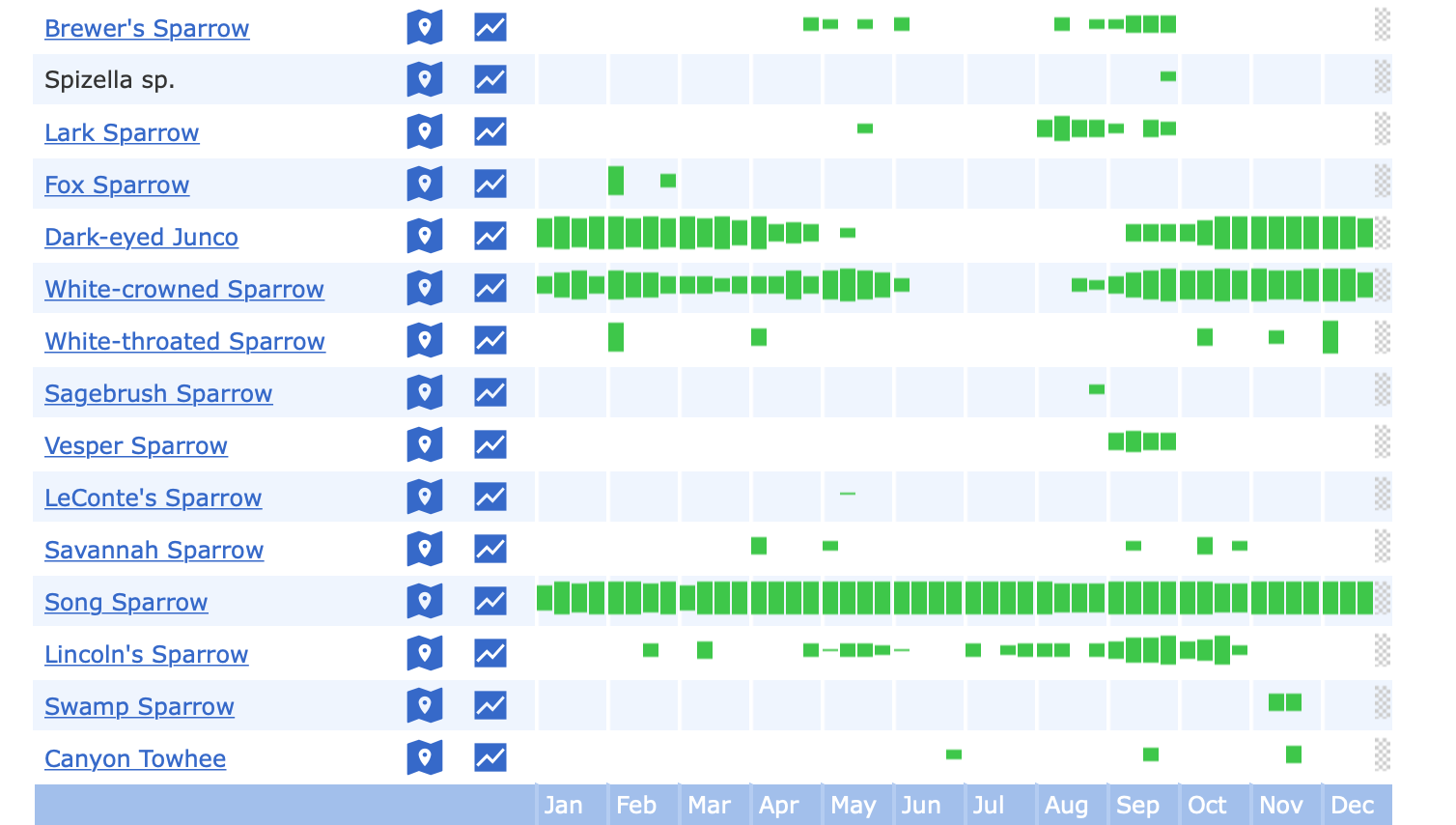

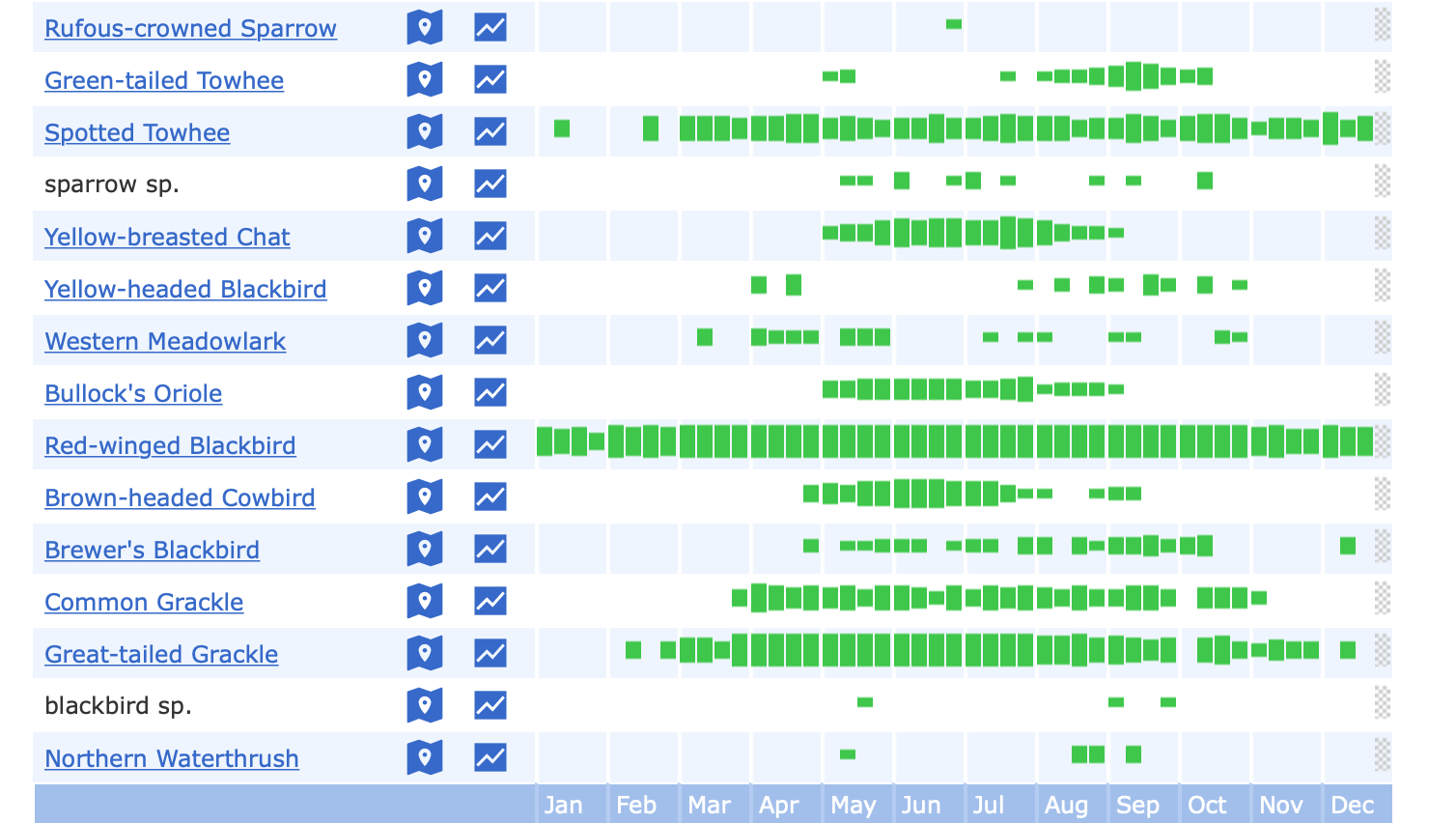

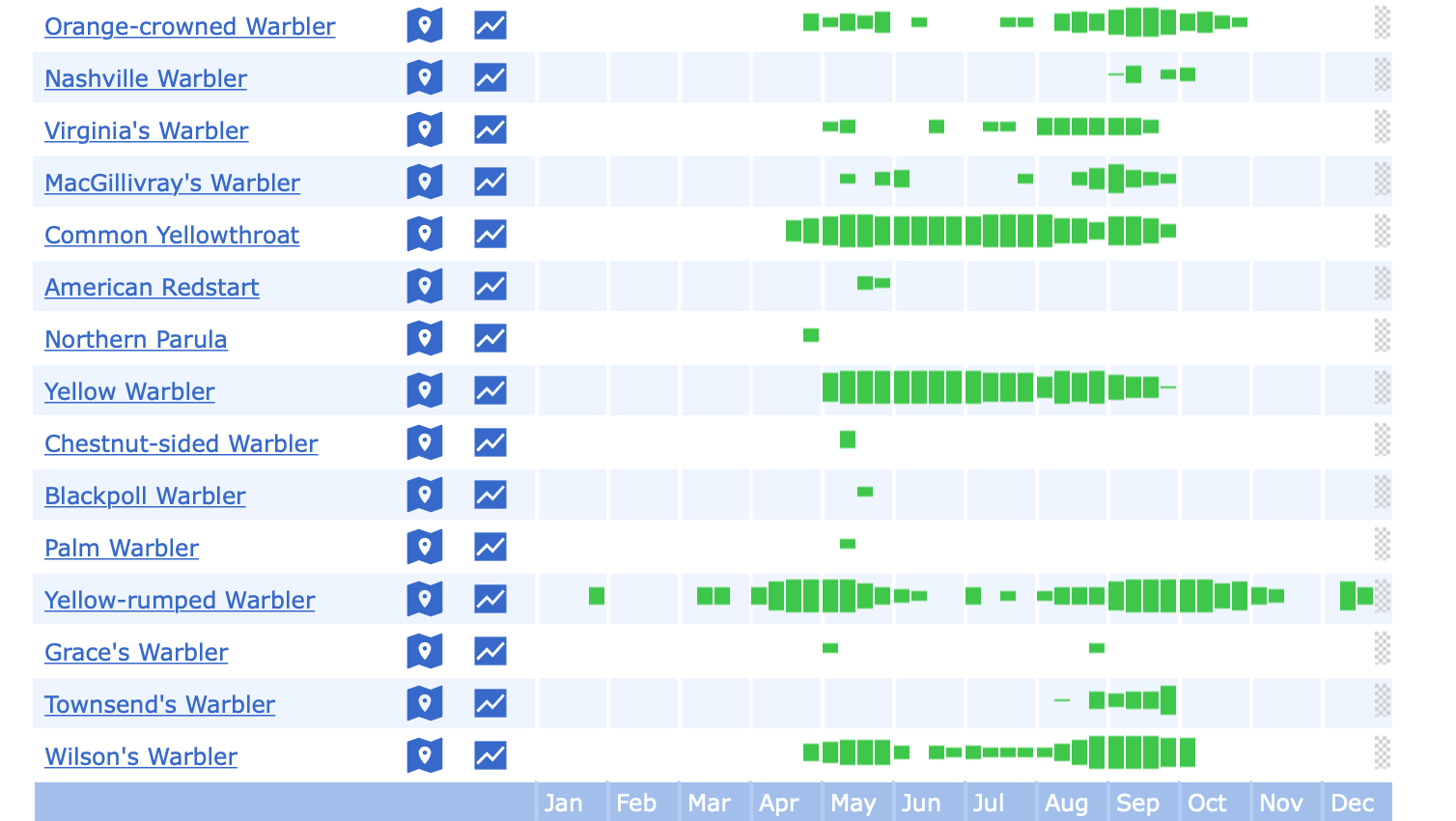

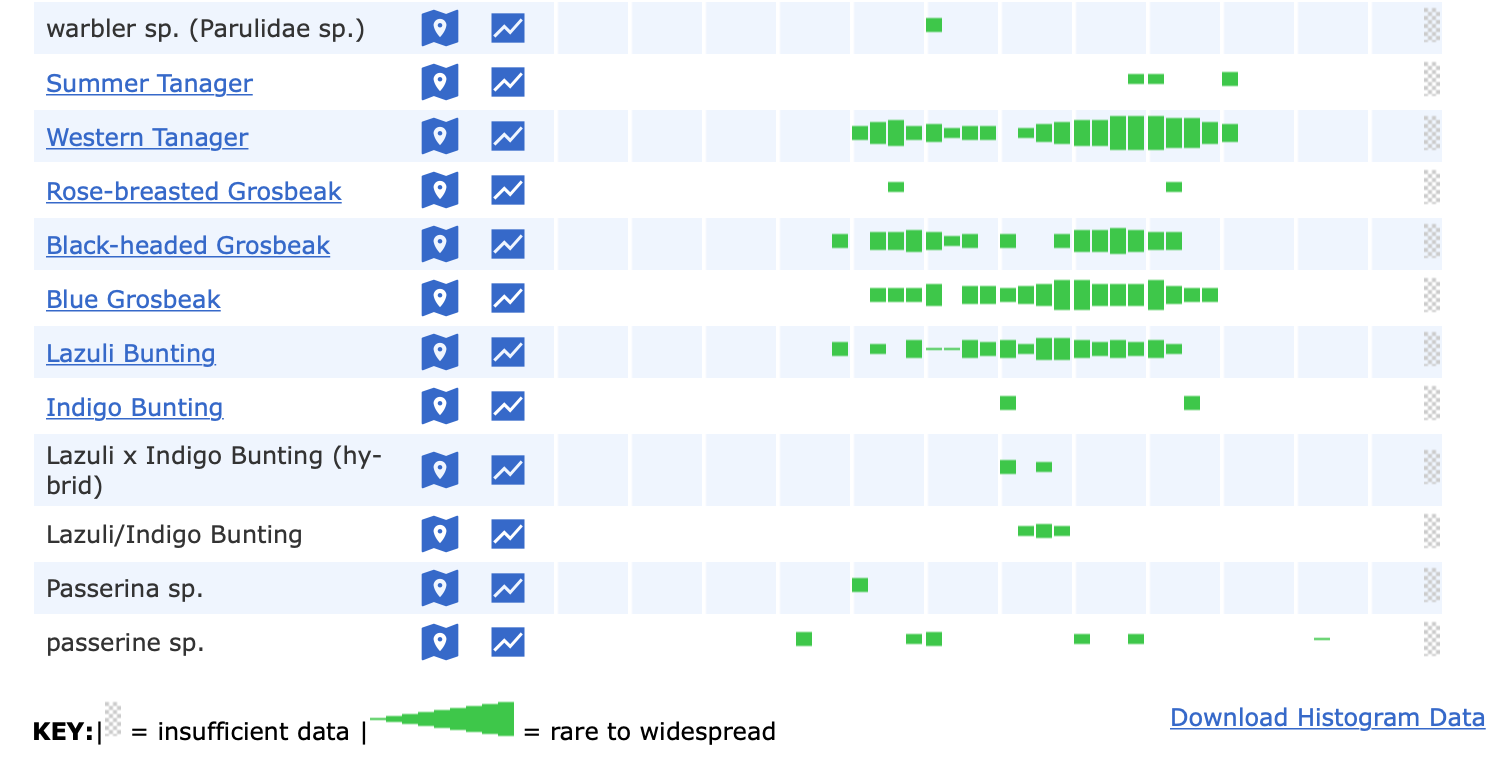

There is another tool that answers the Where? and When? questions in a different format: a Checklist

When you visit many sites (like State or National Parks and Wildlife areas or some Privately Protected Area), the visitor center may offer a printed Checklist showing expected species and their abundances in different seasons.

In this case, the Location is known and the timing is supplied by the Checklist.

eBird provides an electronic version of a Checklist for many locations in the Americas. This tool can be found on the eBird website under the "Explore" tab. It is in the form of a Bar Chart.

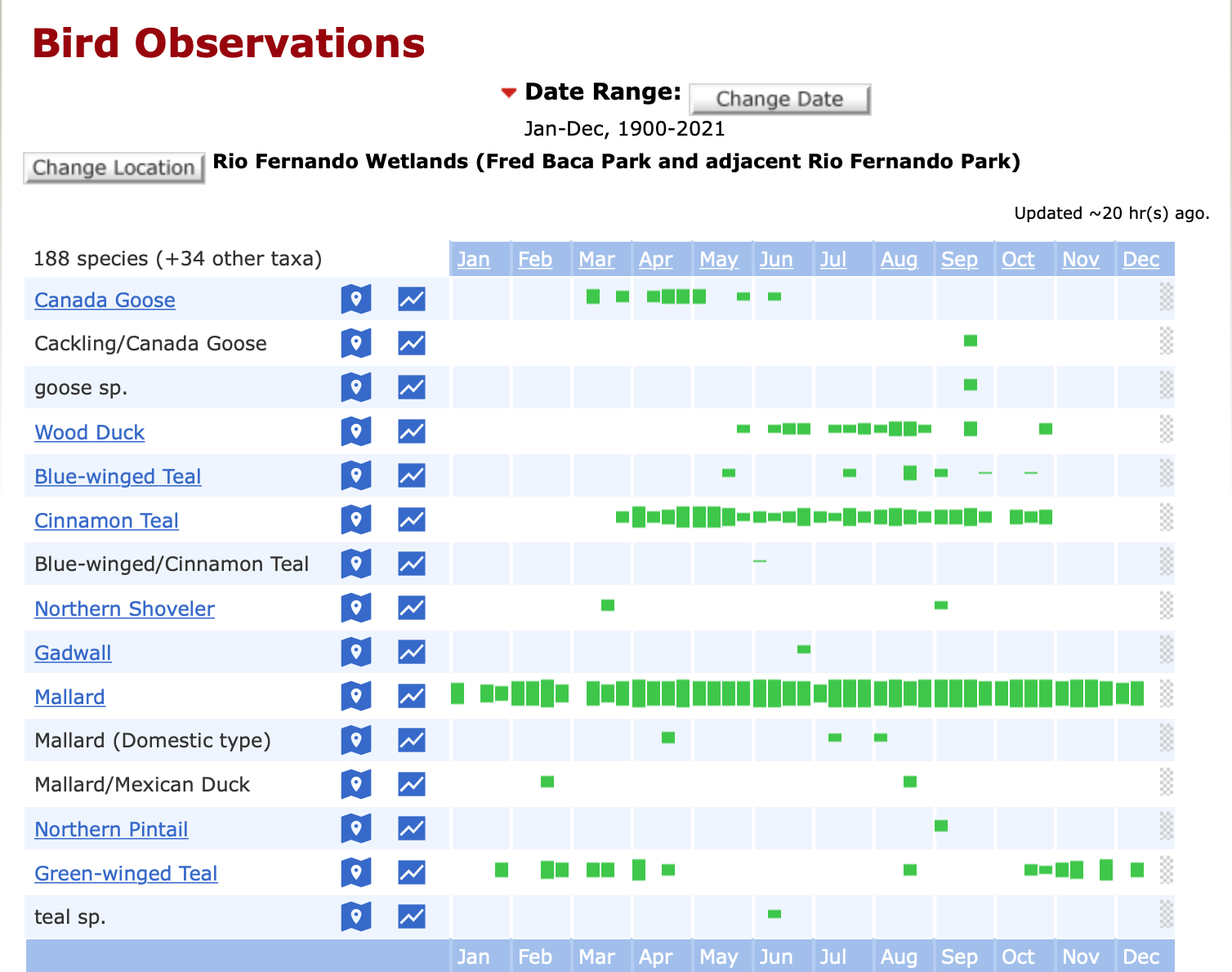

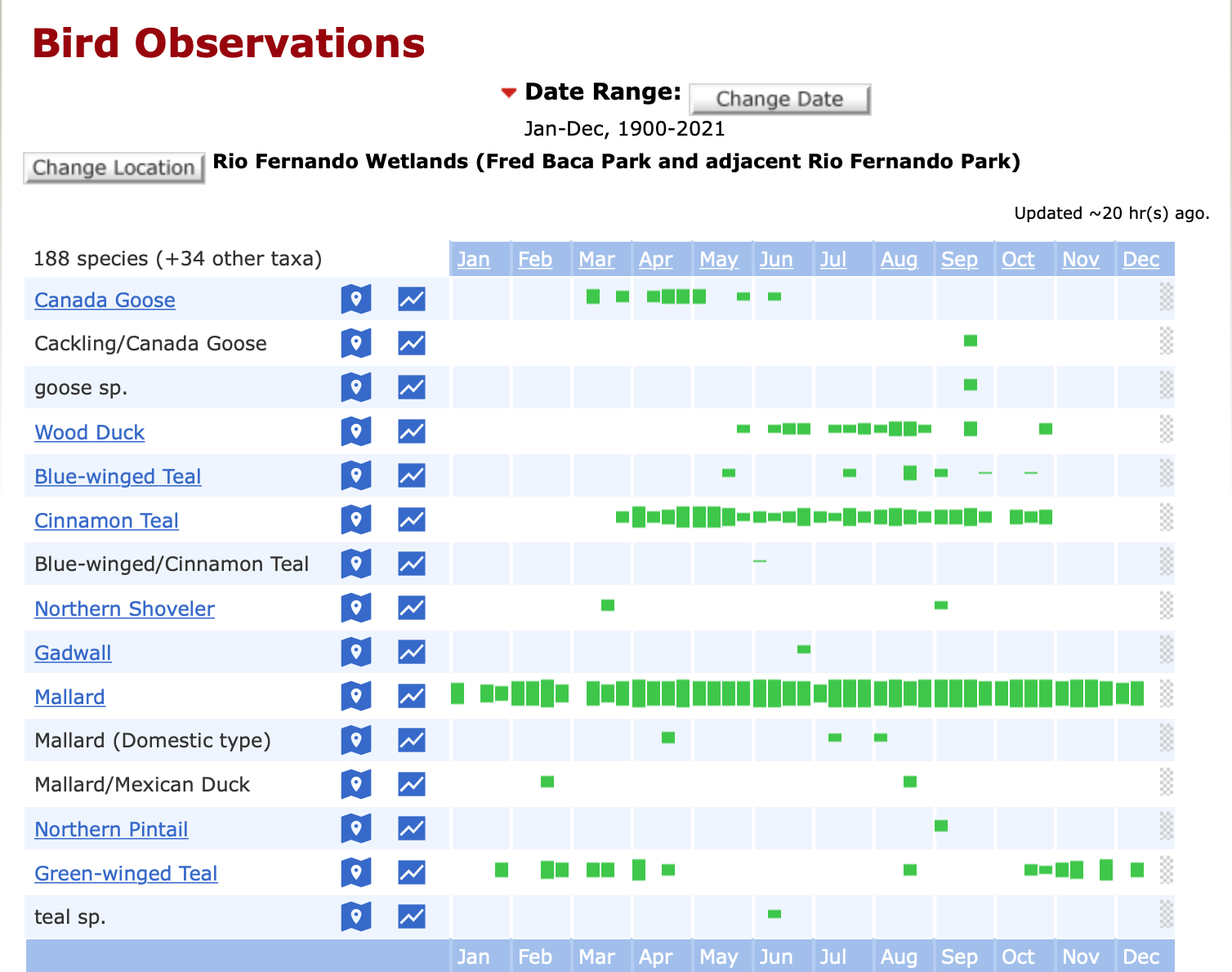

Here are the first rows of the Rio Fernando Wetlands (RFW) eBird Bar Chart with comments:

Find Mallard listed on the left (10th Row).

The green bars indicate that Mallard individuals are present at RFW in every month of the year.

The height of the bars indicates that for much of the year, the species is Common. This species can be classified as a Common Year-round Species.

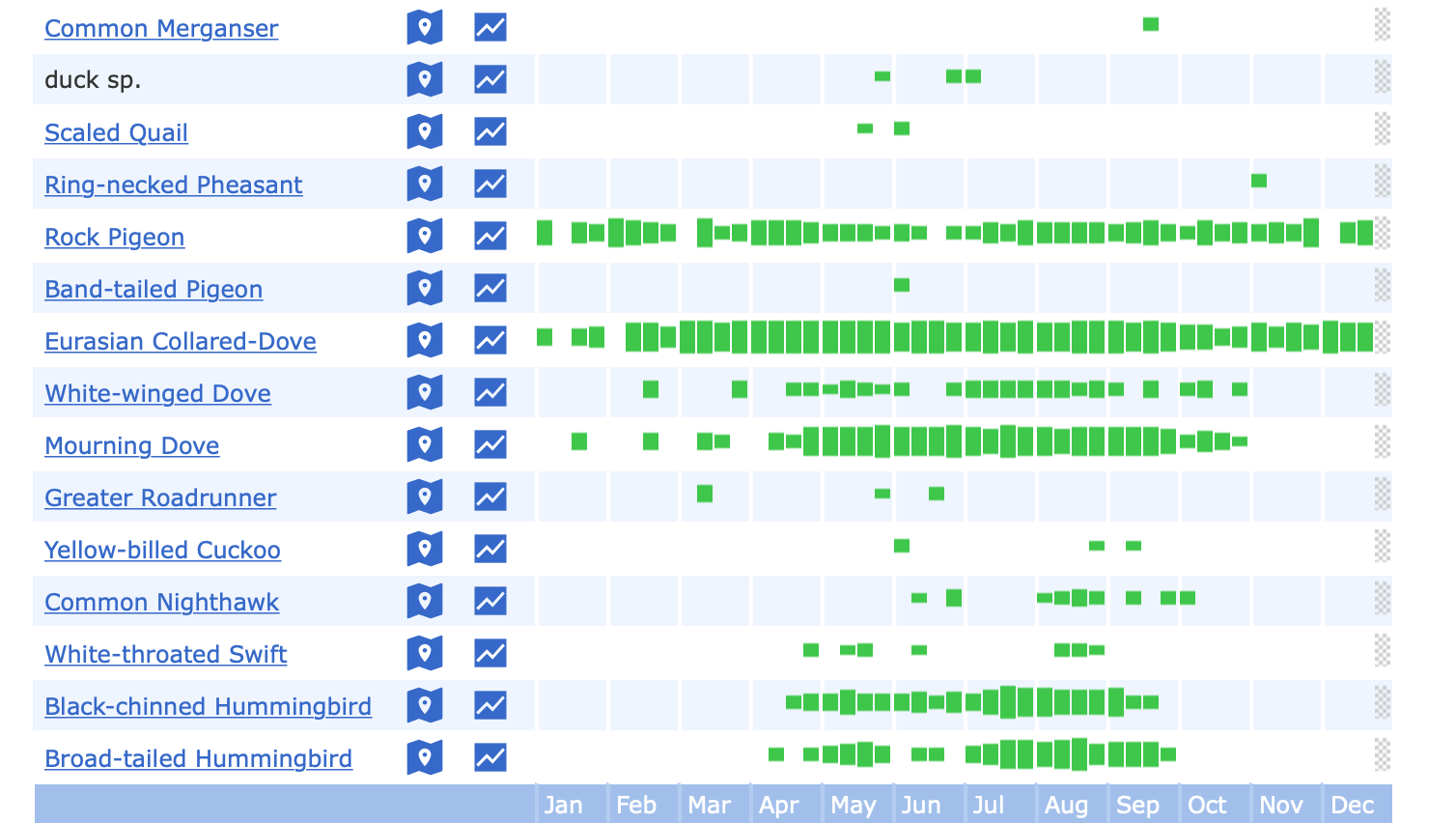

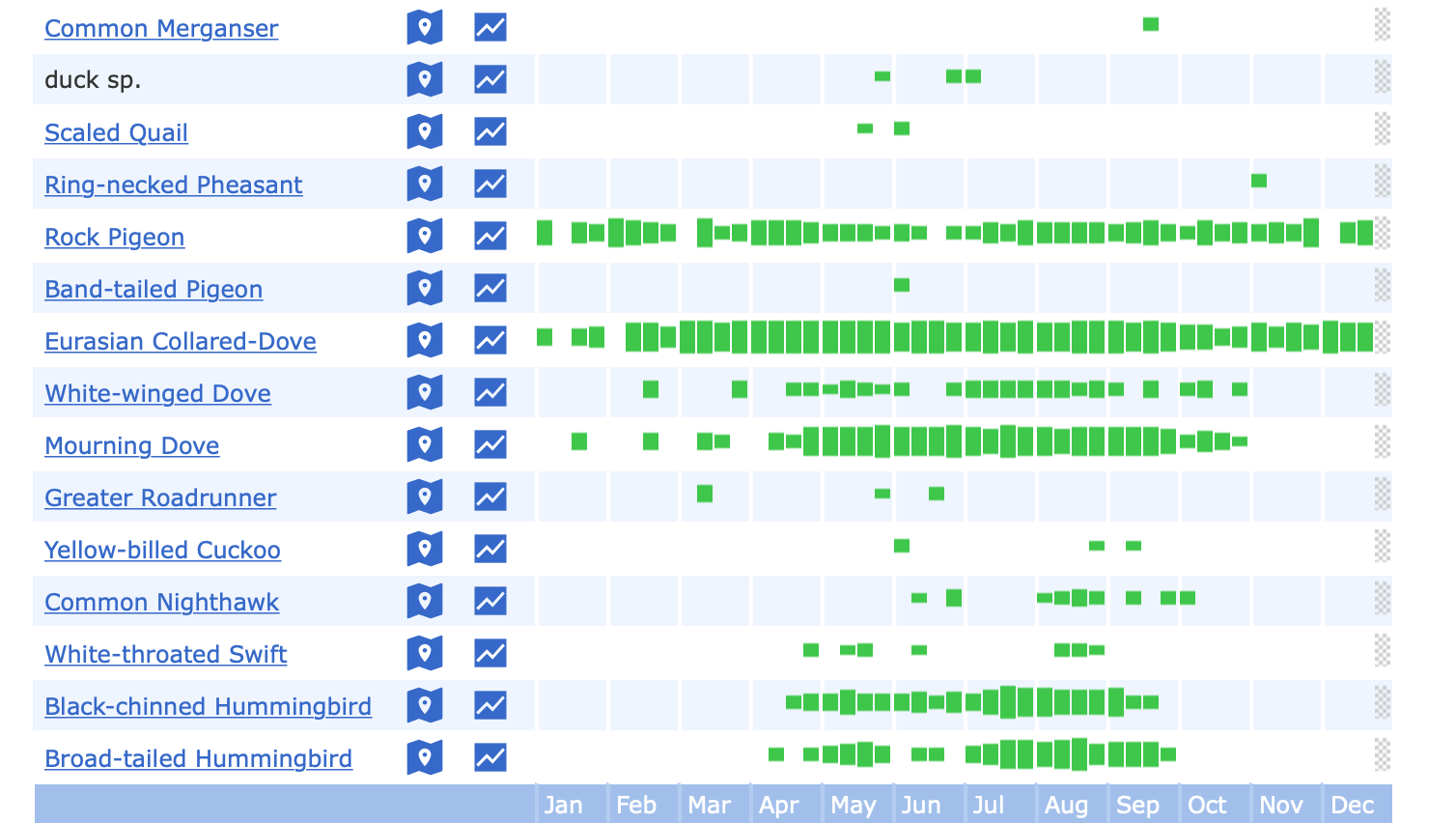

Find Eurasian Collared-Dove in the second block of rows.

This species appears to be a Common Year-Round species. But notice that it is not as common in the Winter.

What about the Black-chinned and Broad-tailed Hummingbirds at the end of the block?

Perhaps these species are migrants? It appears that they arrive in Spring and leave in the Fall.

Both of these species are classified as Migrant Summer Breeders.

The Green-winged Teal seems to be here mostly in the Winter months. Even then, it does not appear to be very common.

This species is classified as an Uncommon Winter Visitor.

The Northern Shoveler has only been recorded a few times at RFW. It has only been recorded during early Spring and early Fall.

Perhaps it should be classified as a Rare Transient

- Common: Almost always seen in suitable habitat and proper season.

- Less Common: Present and seen often, in suitable habitat and proper season.

- Uncommon: Present, but not often seen even in suitable habitat and proper season.

- Rare: Unusual, seen only every 2 to 5 years.

- Vagrant: Seeing these birds is highly unusual. They are out of their normal range.

Why are there species in this list that are not in the RFW Photo and Plain Lists? Many of the records in the eBird Bar Chart are Vagrants which may never again be seen at RFW. A few records may actually represent individuals that were incorrectly identified. They have been removed to simplify the list.

Important Idea:

In reality, the Photo Lists and the Plain Lists on this website are Checklists in the sense that they refer to a particular location (RFW) and give Timing and Abundance information.

Click link to see the RFW-Bar Chart in a Different Form, sorted by Season and also by Abundance:

Without feathers, a bird would be overwhelmed by the extremes of the natural world. In a real sense, feathers act as surrogate for house and home.

Here is a Scaled Quail (Callipepla squamata). Other than the beak, eyes and the bare feet, all other features are formed by feathers:

Different species are distinguished by many features. They include:

- Overall size

- Beak: size, shape and color

- Leg/foot: length and color (actually tarsus/toes)

- Eye color

- Relative Tail length

- Wing shape and Flight style

- Behavior

As you observe birds, get in the habit of noticing all of those qualities. Sometimes just one or two of those features may turn out to be key to an identification.

However, since most of what you see on a bird are its feathers, learning to describe those feathers is very helpful.

Most Field Guides have a page or two on the parts of a bird. You can get some terminology from there. A web-search on "bird parts" or "bird feather groups" will turn up lots of examples.

Here are four bird photos with some basic feather groups marked:

For this Western Bluebird (Sialia mexicana):

- Crown

- Nape

- Mantle

- Throat

- Breast

- Side

- Belly

- Flank

- Vent

- Undertail Coverts

Photo by: Bob Friedrichs

For this Townsend's Warbler (Setophaga townsendi):

- Throat

- Breast

- Side and/or Flank

- Belly

- Vent

- Undertail Coverts

- Wing-bars

- Mantle

- Auricular or Ear-patch

- Supercilium or Eyebrow

Photo by: Bob Friedrichs

For this Nashville Warbler (Leiothlypis ruficapilla):

- Eye-ring

- Throat

- Breast

- Belly

- Vent

- Undertail Coverts

- Weak or Faint Wing-bar

- Mantle

Photo by: Tom Jackman

For this Yellow-rumped Warbler (Setophaga coronata):

- Split Eye-ring

- Mantle

- Rump

- Flank

- Side

- Throat

- Yellow Crown-patch

Masks:

Common Yellowthroat:

Loggerhead Shrike:

Cedar Waxwing:

Eye-brow (Supercilium):

Red-breasted Nuthatch:

Photo: Bob Friedrichs

Bewick's Wren:

Rump Patch:

In these three species, the rump-patch is often used for ID

Northern Flicker:

Northern Harrier:

Cliff Swallow:

Photo: Tom Jackman

Central Spot (Breast):

In some situations, the presence or absence of a central spot is a key to an ID

Song Sparrow: Central spot on streaked breast

Lark Sparrow: Central spot on clear breast

Sparrow Face/Head Patterns:

Lincoln's Sparrow:

Photo: Steve Knox

Chipping Sparrow:

White-crowned Sparrow:

Lark Sparrow:

Brewer's Sparrow:

Photo: Tom Jackman

Savannah Sparrow:

Bill Length:

Here is a case where bill length is often used to separate two species:

Hairy Woodpecker with bill length (from base to tip) about equal in length to head (from bill base to nape).

Downy Woodpecker with bill much shorter than the length of the head from front to back.

The Hairy is a larger bird overall than the Downy, but it is not always possible to get a sense of the size of either species in the field.

It IS almost always possible in the field to "measure" the bill size against the head size.

Learning to recognize birds by their sounds is an inevitable outcome of spending time in the field consciously looking and listening. Over time, for most species, you will have the opportunity to see individuals making their sounds.

The process is not quick. But eventually, both bird vocalizations and other bird sounds, like hammering, will begin to evoke an image in your mind of who is making that sound.

Some useful strategies:- Study recordings:

- Online Field Guides and Smart Phone Apps are excellent for hearing the details of a particular vocalization. These recordings are made in the field using equipment to isolate the sounds of interest.

- Listening to sounds on Xeno-canto.org will often provide recordings with the target species less isolated. This more closely emulates the field experience.

- Trying to notate the sound using dots, dashes, up-turned lines, squiggles, etc. can help to solidify the details.

- Take it slow! Choose a few species common at that time of the year and focus on those species both in your study and in the field. Add species as it becomes comfortable.

- When you hear a sound you don't recognize, focus on listening to the tonal quality as well as the note-by-note details.

- Devote a particular bird outing to learning a particular species sounds.

When an unfamiliar birdsong is pointed out to a novice birder, it is common for the novice to report that they "can't hear it". Once a singing bird is noticed, a common practice among birders is for everyone to fall completely silent and watch the hand of whoever heard the bird. As soon as another vocalization begins, the hand is moved with a flick of the wrist as a signal (sometimes in the direction of the sound). After a few vocalizations, the novice birder who "couldn't hear it" often begins to hear it.

Once one's ears are tuned into a few sounds, hearing new sounds becomes easier and easier.

The examples below are intended to begin to attune your listening to hearing bird sounds.

Here are three common types of birdsong:

Whistle or shriek:

The repeated high whistle of a Townsend's Solitaire:

A single call of a Black-crowned Night-Heron:

The cry of a Red-tailed Hawk:

Trill:

The long, dry trill of a Chipping Sparrow:

The subtle trill of the Orange-crowned Warbler (Yes, warblers don't warble!):

Warble:

Song of the Warbling Vireo:

Our most widely heard bird that warbles: House Finch

If you are surprised about Warblers not warbling, go over to All About Birds and listen to a few warblers.

Most Warbler song consists of whistles (often delivered at a fast pace and varied pitches) and trills (often very fast).

Similarities among Songs:

The song of the American Robin is well known to many people. A common mnemonic for the song is often given as: "cheeri-up cheer-a-lee cheer-ee-o" sometimes followed by a "whinny".

Birders often refer to sounds of other species as being similar to the sounds of Robins. Common examples are Western Bluebird, Mountain Bluebird, Townsend's Solitaire, Western Tanager, Black-headed Grosbeak, and Plumbeous Vireo.

Here is the Robin song compared with two of those species:

Song of the American Robin.

Note the pace of the song and the individual phrases.

Here is the song of the Black-headed Grosbeak.

The song consists of similar short phrases but is "more continuous and more melodic" than the Robin song.

Here is the song of the Plumbeous Vireo.

The song has Robin-like phrases separated by much longer pauses.

Mnemonics: Another Approach

There are many mnemonics used by bird-watchers to help remember the song of some species. They are usually just a few syllables that capture something about the rhythm and tonal sense of the song.

Here are four well known examples. It may be useful to say each one a few times and then go to All About Birds or some other source and listen to a recording of the song.

- White-winged Dove: Who cooks for you? (The 2nd song given fits the best.)

- Yellow Warbler: Sweet, sweet, sweet, I'm so sweet.

- Lazuli Bunting: Paired notes: Fire Fire Where? Where? Here Here See it?

- Common Yellowthroat: Witchety witchety witchety

Spotted Towhee Song Immersion:

Here is a 16-minute recording made in Dixon, NM on July 28, 2006 shortly after sunrise. The primary singer is a Spotted Towhee (very prominent). The main singer in the background, giving a range of whistles and trills, is a Yellow-breasted Chat. There is another Spotted Towhee that occasionally is heard from further away.

After 13 minutes, the primary singer leaves the original location. It is not known if the more distant Spotted Towhee song after that is by that same individual.

Note how the song note order and phrasing changes over time, while the tonal quality (timbre) of the sound remains constant.

Observing bird behavior is essentially answering the question "What is the bird doing?"

Answering the question can help with identification of a species but the behavior is usually interesting on its own. Bird behavior is a large field unto itself. Field guides often provide a few details if the behavior helps in identification. There are many excellent books on bird behavior. You may find them interesting reading and your bird-watching experience will be enhanced.

Here is a list of some behaviors that are commonly observed by bird-watchers. It is offered as an encouragement to pay attention to every aspect of a bird during an observation.

- Feeding:

- Flycatcher leaving a perch to catch a flying insect and then returning to the exact same perch.

- A Spotted Towhee "tossing" leaves around under a shrub to expose insects.

- Swallows flying continuously, dipping and turning, catching insects as they fly.

- A Warbler gleaning small insects off of the small branches of a Cottonwood.

- An adult feeding food to a juvenile offspring.

- A Black-capped Chickadee eating sunflowers while hanging upside down from a blossom.

- A Hummingbird working its way done a row of flowers in the garden, stopping to feed at each plant.

- Mobbing:

- Ten to Thirty Crows and Magpies making a racket while diving at and eventually driving away a raptor.

- A pair of Cassin's Kingbirds noisily driving away a Jay from their nest site.

- Unique Flight features:

- A long stream of Crows flying downslope in the morning and upslope in the evening.

- A Red-tailed Hawk circling around without flapping, gaining altitude on rising air.

- A group of 16 Common Raven swirling around in a "kettle" (soaring on rising air) like raptors.

- Yellow-breasted Chat calling while slowly descending in a "hovering" kind of flight.

- Pair of White-throated Swift clinging together and tumbling hundreds of feet, releasing each other before hitting the ground.

- A male Hummingbird making a "dive display": Diving down towards where a female is perched and pulling out of the dive just above the female.

- Birds carrying nesting materials.

- Mixed Flocks:

- During the breeding season, birds are aggressively defending feeding territories. In the winter, the birds often join in mixed foraging flocks.

- Uncommon foraging patterns:

- White-breasted Nuthatch walking down a tree head-first.

- Brown Creeper gleaning from the surface of a tree in a spiraling motion, climbing upwards while walking around the circumference of the tree. Once a trunk is ascended, the individual flies to the base of the trunk of a nearby tree and repeats the process.

- Hammering:

- Woodpecker hammering on a hollow branch to increase the intensity of the sound.

- Woodpecker hammering on a metal ladder, apparently to increase the instensity of the sound.

- Here is a link to a video of a Northern Flicker whinnying and hammering on the cap of a stove pipe.

- Preening:

- All birds spend some time each day making sure that their feathers are aligned properly. This is usually done with the bird's bill.

- Occasionally birds will preen other birds.

Every species has a unique Family History. That history is "who" that bird is.

- What family grouping is it in and what is the family's evolutionary history?

- What Habitats does is utilize for feeding, for breeding or for over-wintering?

- What behaviors does it exhibit and how are they related to its Habitats?

- How does its body size, shape and bill shape relate to its Habitats?

- What does it eat?

- What kinds of sounds does it make and are there special behaviors associated with the sounds?

- Does it migrate? If so, short distance or long distance?

The Life History of a species ties everything together.

Here is a list of common family groupings of bird species regularly seen at the Rio Fernando Wetlands:

- Swans, Geese and Ducks

- Upland Game Birds

- Grebes

- Pigeons and Doves

- Cuckoos and their Allies

- Nightjars, Nighthawks and Swifts

- Hummingbirds

- Gruiformes: Coots, Cranes and Rails

- Smaller Wading Birds

- Gulls, Terns and Skimmers

- Medium to Large Waterbirds: Pelicans and their Allies

- Long-legged Wading Birds

- Diurnal Raptors: Vultures, Eagles and Hawks

- Nocturnal Raptors: Owls

- Kingfishers

- Woodpeckers

- Falcons

- Tyrant Flycatchers

- Shrikes and Vireos

- Jays, Crows and their Allies

- Larks

- Swallows

- Chickadees and their Allies

- Nuthatches and Creepers

- Wrens

- Gnatcatchers

- Dippers

- Kinglets

- Thrushes and their Allies

- Mimids "Mimic Thrushes"

- Starlings and Mynas

- Waxwings

- European Passerines

- Wagtails and Pipits

- Finches

- Sparrows and their Allies

- Chats

- Icterids: Blackbirds, Orioles and their Allies

- Wood-Warblers

- Tanagers

- Grosbeaks (Cardinalidae)

- Buntings

Species within a family are genetically closely related. Family members have many characteristics in common.

You might not be able to distinguish between two different hummingbird species, but you're not going to mistake a hummingbird for a Hawk:

- Different families, different characteristics!

So family groupings reflect the genetic background of its members and at the same time, provide a tool for learning to identify species:

- Identifying birds to the family level is an important step!

Why do the families appear in the order shown? Wouldn't an alphabetical list be easier to use?

The list appears in "taxonomic" order. Taxonomy is a system of naming and classifying all living things. It reveals the genetic relationship among all of life.

Deep in the evolutionary past (~240 Million Years Ago) the evolutionary paths of Birds and Crocodiles (and Caimans) diverged. Crocodiles continued to evolve into the crocodile families of today. Birds continued to evolve into the bird families of today.

All bird families share a common ancestor somewhere along their evolutionary path. The genetic strains (orders) that led to some families diverged onto their separate paths earlier in time than others.

It is the order of those divergences that is reflected in this list and in most Field Guides.

It is easy to fall into thinking that the "later" families are somehow "more evolved" than the "earlier" ones. All present-day species trace their lineage back to the bird/crocodilian split. No species is "more" or "less" evolved. In terms of time, all lineages have been evolving the same length of time. Each lineage has evolved in coordination with the habitats it utilizes. Thus, the branches of the evolutionary tree are simply an expression of the diversity of life.

Here is the same list of families, but with a division between those that developed earlier and later:

Non-Passerines:

- Swans, Geese and Ducks

- Upland Game Birds

- Grebes

- Pigeons and Doves

- Cuckoos and their Allies

- Nightjars, Nighthawks and Swifts

- Hummingbirds

- Gruiformes: Coots, Cranes and Rails

- Smaller Wading Birds

- Gulls, Terns and Skimmers

- Medium to Large Waterbirds: Pelicans and their Allies

- Long-legged Wading Birds

- Diurnal Raptors: Vultures, Eagles and Hawks

- Nocturnal Raptors: Owls

- Kingfishers

- Woodpeckers

- Falcons

Passerines:

- Tyrant Flycatchers

- Shrikes and Vireos

- Jays, Crows and their Allies

- Larks

- Swallows

- Chickadees and their Allies

- Nuthatches and Creepers

- Wrens

- Gnatcatchers

- Dippers

- Kinglets

- Thrushes and their Allies

- Mimids "Mimic Thrushes"

- Starlings and Mynas

- Waxwings

- European Passerines

- Wagtails and Pipits

- Finches

- Sparrows and their Allies

- Chats

- Icterids: Blackbirds, Orioles and their Allies

- Wood-Warblers

- Tanagers

- Grosbeaks (Cardinalidae)

- Buntings

Remember that the list is ordered by time on the evolutionary path.

Thus, the families backed in white represent earlier evolutionary development.

The families backed in green represent later evolutionary development.

- Most of the Non-passerine strains (Orders) were present by about 50 million years ago.

- Most of the Passerine strains (Orders) were present by about 35 million years ago.

So what is the evolutionary development that separates the later, "Passerines" from the earlier, "Non-passerines"?

One important development is that Passerines have a different arrangement of the toes on the feet and the toes have a different connection to the tendon that closes the bird's foot.

When the bird's knee is bent, the tendon causes the foot to curl and lock around a branch or a wire that a bird lands on. This is not true for the Non-passerines.

- So:

- Non-passerines have only vountary perching. It requires conscious activity.

- Passerines can use invountary perching. Allows them to easily sleep standing on a branch.

Another important development is that Passerines have a more complex musculature for controlling their Syrinx, the sound making structure. This is especially pronounced in the families coming after the Flycatchers. These later passerines (Oscines) are commonly referred to as "Songbirds" because of their ability to produce very complex songs.

What does all of this have to do with bird identification? Bird species can be categorized in many different ways. For now, keep in my mind:

- All species fit into a family grouping.

- All families share characteristics

Field Guides provide the bare outline of a species' Life History.

The Cornell Lab's site "All About Birds" provides a more complete Life History.

Cornell's subscription site, "Birds of the World" (Formerly "Birds of North America Online") provides detailed histories written by academic ornithologists based on wide surveys of the scientific literature.

Wikipedia should not be overlooked as a source for detailed information on North American and other bird species. The individual species accounts are often extensive, detailed, footnoted and always with a list of references for further study.

Here are links to several Wikipedia species accounts to give you a flavor of this very useful resource:Birder's Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds is an excellent source of detailed information on North American Birds. Though it is a little dated (Published in 1988), it provides detailed information in a very concise format. Want to know how many days from egg-laying to fledging for a species? What kind of nest it makes? Its food sources? It is a valuable resource.

Details: Birder's Handbook: A Field Guide to the Natural History of North American Birds by Paul Ehrlich, David S. Dobkin, and Darryl Wheye. (Simon and Schuster) 1988

So far, we have used two categories to group birds: Families and Season.

- Seasonal groupings are based primarily on migratory behavior of species.

- Family groupings are based on genetic relationship.

Family groupings help with identification of birds since birds in the same family have many shared characteristics.

But birds in the same family can also have significant differences.

There is another layer of classification within each family: genus (genus is the singular, genera is the plural). So each family has more than one genera.

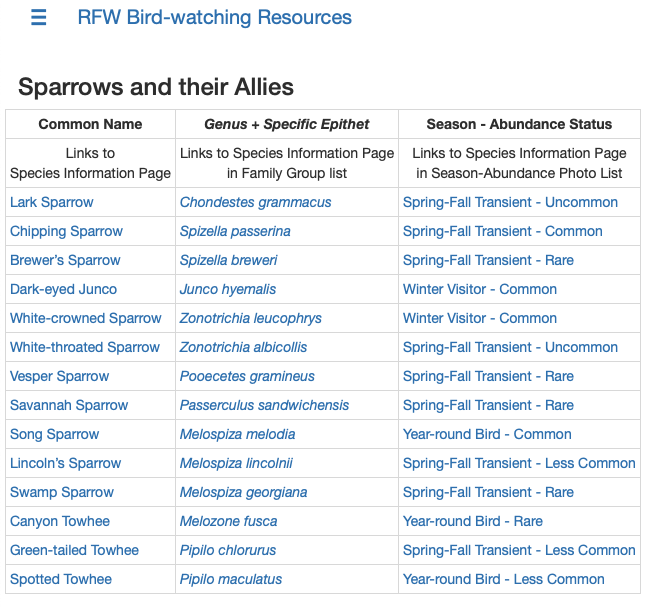

If you go to the "Bird List" page of this site you can generate the following list for the sparrow family:

There are 14 species in the list. But there are only nine different genera.

Find the Chipping and Brewer's sparrows in the beginning of the list.

The scientific name for Chipping Sparrow is Spizella passerina. Spizella is the genus. Note that the Brewer's Sparrow is also in the genus Spizella.

However, the second part (specific epithet) of the scientific name is different for the two birds. The combination of the genus and specific epithet identifies one, and only one species.

- The Chipping Sparrow is in the Sparrow Family and in the Spizella genus. Its unique name is Spizella passerina. No other living thing (be it plant, tree or animal) has that two-part name.

- The Brewer's Sparrow is in the Sparrow Family and in the Spizella genus. Its unique name is Spizella breweri. No other living thing (be it plant, tree or animal) has that two-part name.

Note that in the RFW list of Sparrows, there are two species in the genus Zonotrichia, three in the genus Melospiza and two in the genus Pipilo.

So what does this have to do with bird-watching?

In the same way that identifying birds to the Family level can be useful, identifying birds to the Genus level can be useful.

You may find it instructive to go to the "Photo Bird Lists" page and look at the 14 Sparrow species. Note similarities within each genus and differences between genera.

Sometimes it's just not possible to identify a bird to the species level. This happens for all level of birders.

However, in many cases it is still possible to identify the bird to the Family or to the Genus level.

- If you are keeping records for yourself, these ID "problems" can be a great source of learning.

- If you are also entering your observations on eBird, ID to the Family or Genus level is valuable information and eBird encourages you to do so!

[Beginners: Keep in mind that on eBird you always have the option of leaving an unidentified bird off the list.]

"spuh" refers to "sp.", an abbreviation for species.

These two categories are commonly used when there are three or more possible species within a family or genus:

- The left column shows the usage for ID to the Family level. Example: sparrow sp.

- The middle column shows the usage for ID to the Genus level. Example: Empidonax sp.

"slash" refers to "/", used to indicate identification to a Species-pair.

This category is used when there are only two possible species within a family or a genus at a particular location.

Two examples follow:

Here are photos of two different species: a Sharp-shinned Hawk and a Cooper's Hawk.

If you study a field guide or go to the "Photo Bird List" page you will see that these two species are very similar. There are subtle differences, but there is also overlap even in the differences.

Even among very experienced birders, there can be disagreement as to which species is being observed.

An observed individual could be identified as a "hawk sp.", but generally it is not difficult to know that it is in the accipiter genus (very different flap-glide pattern and size than other hawks).

The individual could also be identified as "Accipiter sp.", as there are three accipiters in our area.

However, the third species is rare at RFW as it is generally a higher altitude bird and is usually easy to tell apart from the Cooper's and Sharp-shinned.

So, at RFW, usually the best option will be to record the individual as "Sharp-shinned/Cooper's Hawk".

An important point: This is not a guessing game. If you are not sure about an ID, the responsible thing (as a Citizen Scientist) is to report the individual as either a "spuh" or a "slash"!

Mountain Chickadee:

Here are two species from the same genus (Poecile) that are quite easy to distinguish visually. However, at times you may hear a chickadee without seeing it. Here is another case where either a "spuh" or "slash" is called for.

There are other species in its "Poecile" genus, but only one occurs in NM and it is found only in the extreme southwest corner of the state.

So, at RFW one should use the Species-pair: Black-capped/Mountain Chickadee.

Some thoughts about why people watch birds. You probably have others!

- Birds are beautiful.

- Birds are interesting.

- Birds are great singers.

- The act of birding brings one into sensitive connection with the living world.

- Birds are Hunter-gatherers. In our past, we were too.

- Birds are long-distance travelers: migrants following the seasonal flux of available food.

- Birds are distributed based on geography and habitat, not political borders.

- Birds are part of the diversity of species with whom we are interdependent for survival.

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to Enlarge

Click Map to Enlarge