Conserving Birds

There's only One Web of Life! We all Share One Life Support System!

In times of change, resiliency is a key strength.

Three things that lead to ecological resiliency:- Diversity of Species

- Diversity of Habitats

- Connectivity across Habitats at all Scales

All life on earth is genetically related. Life is a vast multi-generational web that includes every living thing. That web includes us, and it includes birds. Deep in our evolutionary pathway we share a common ancestor with the birds. We are literally cousins!

At a point roughly 320 million years ago, our evolutionary paths diverged. We followed the evolutionary path of the Mammals. The birds followed the evolutionary path of the reptiles and lizards. As we are a result of the 320 million years of evolution on our path since then, so the birds are a result of those 320 million years of evolution on their path.

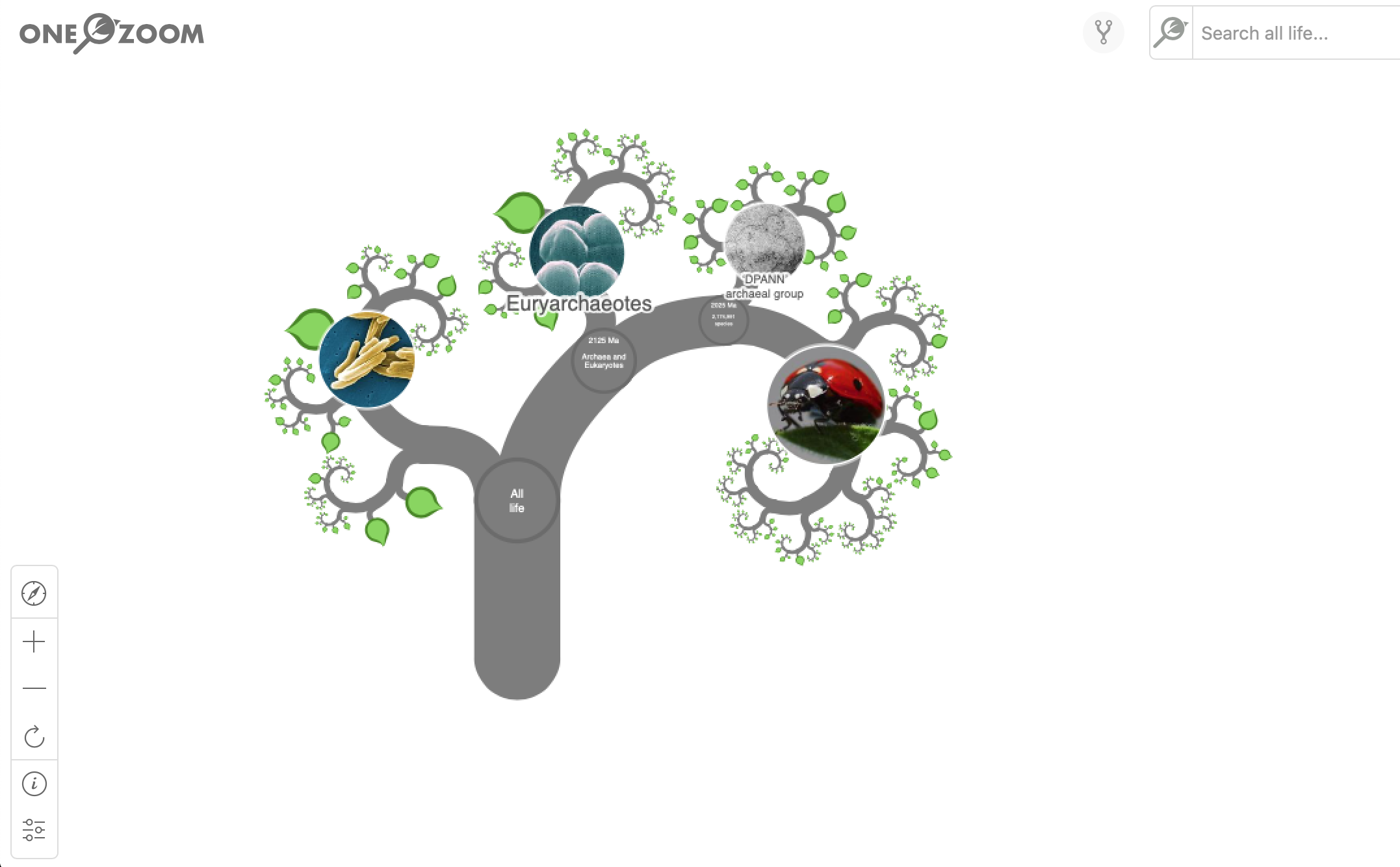

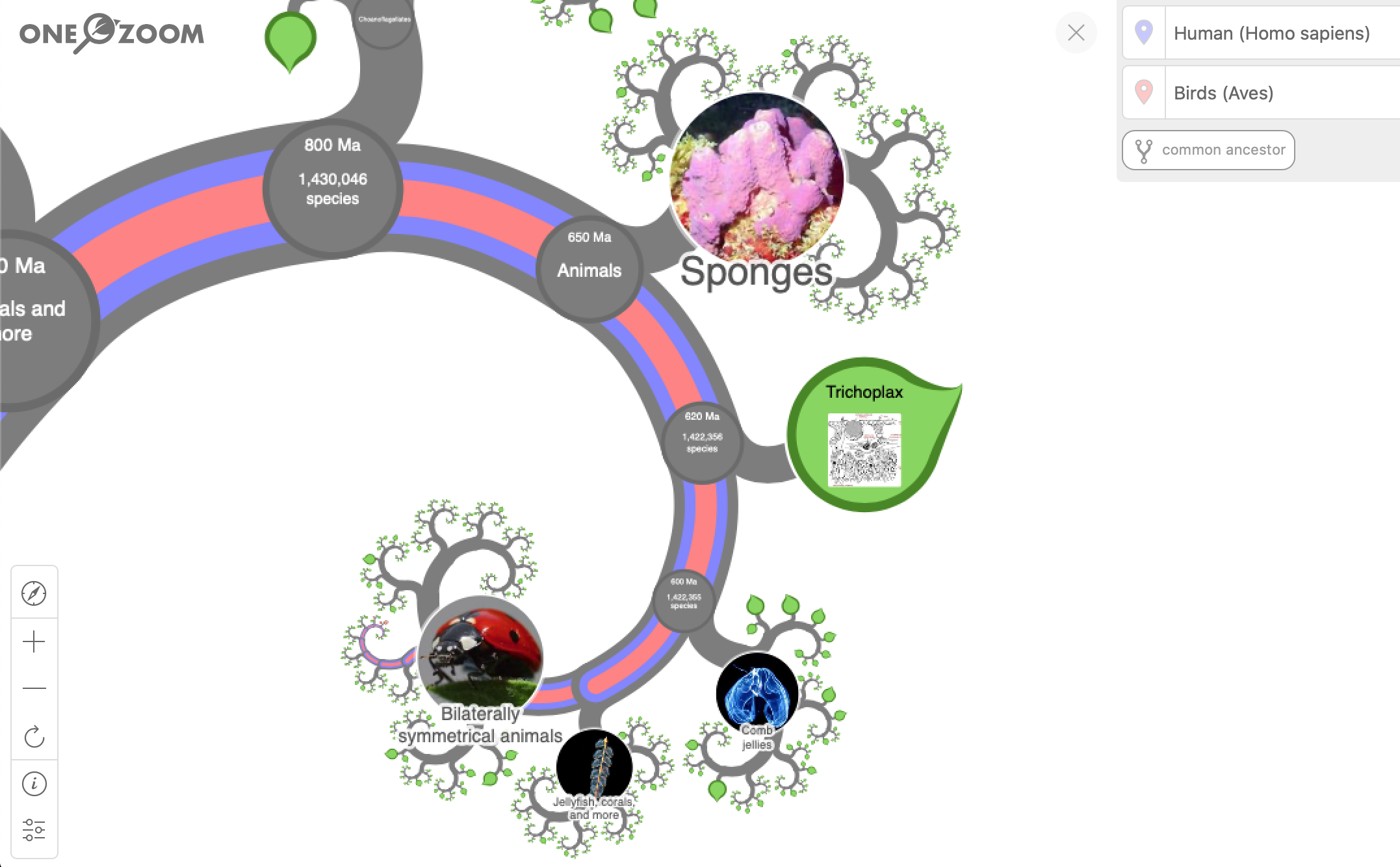

The following images are from the Tree of Life Explorer at OneZoom.org*. The data driving the Explorer comes from the Open Tree of Life, a collaboration of 10 scientific institutions funded by the National Science Foundation.

The Tree of Life presents the current knowledge in the ongoing exploration of the evolutionary links between all of life.

Visit OneZoom.org to further explore life on Earth.

*OneZoom Core Team (2020). OneZoom Tree of Life Explorer Version 3.4.1 URL: http://www.onezoom.org

Here is a tree of life.

All life on Earth is on the same tree.

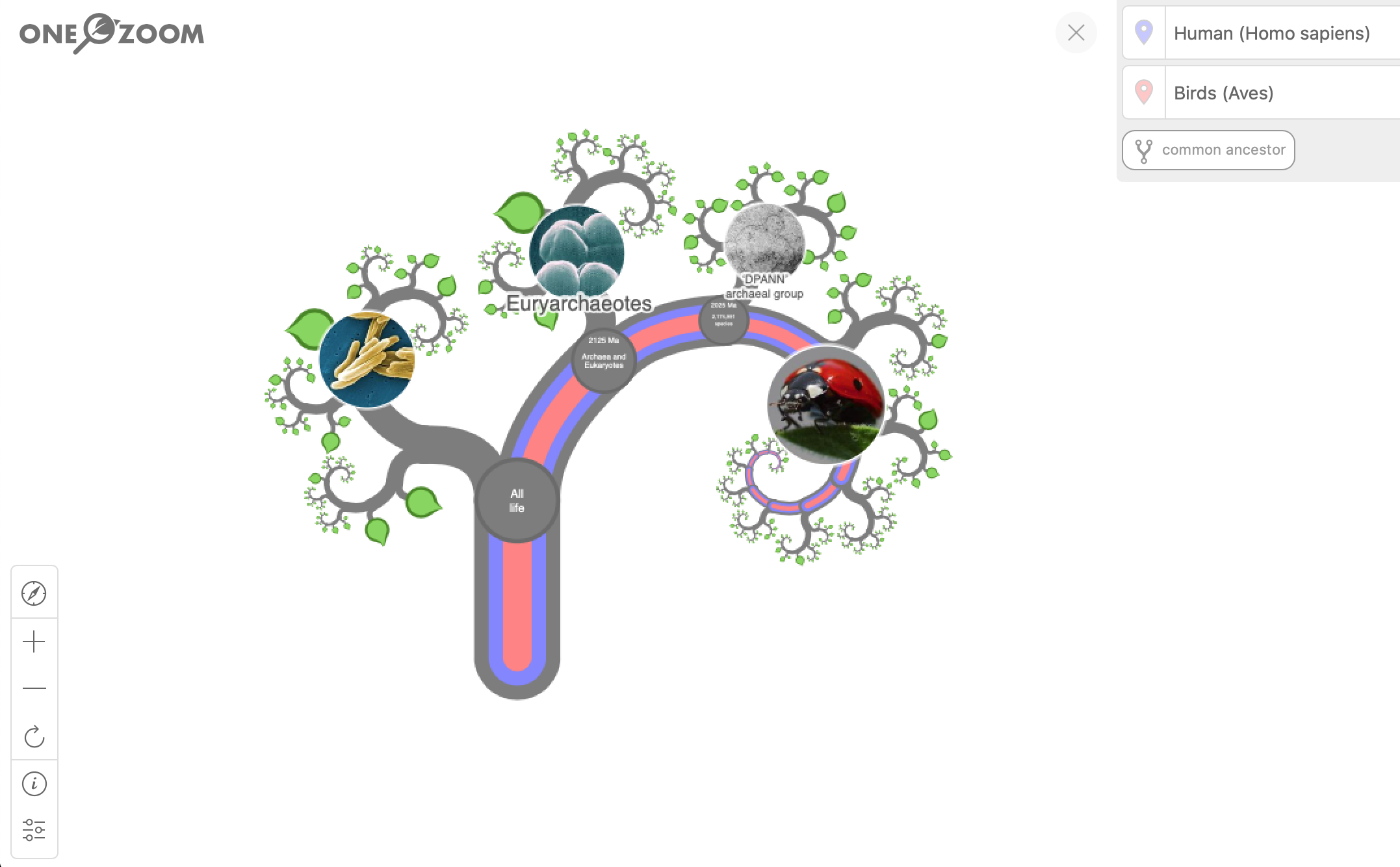

Here is the same tree, but now there are two "traces" shown.

Blue: traces the path of Human evolution from the beginning.

Red: traces the path of Bird evolution from the beginning.

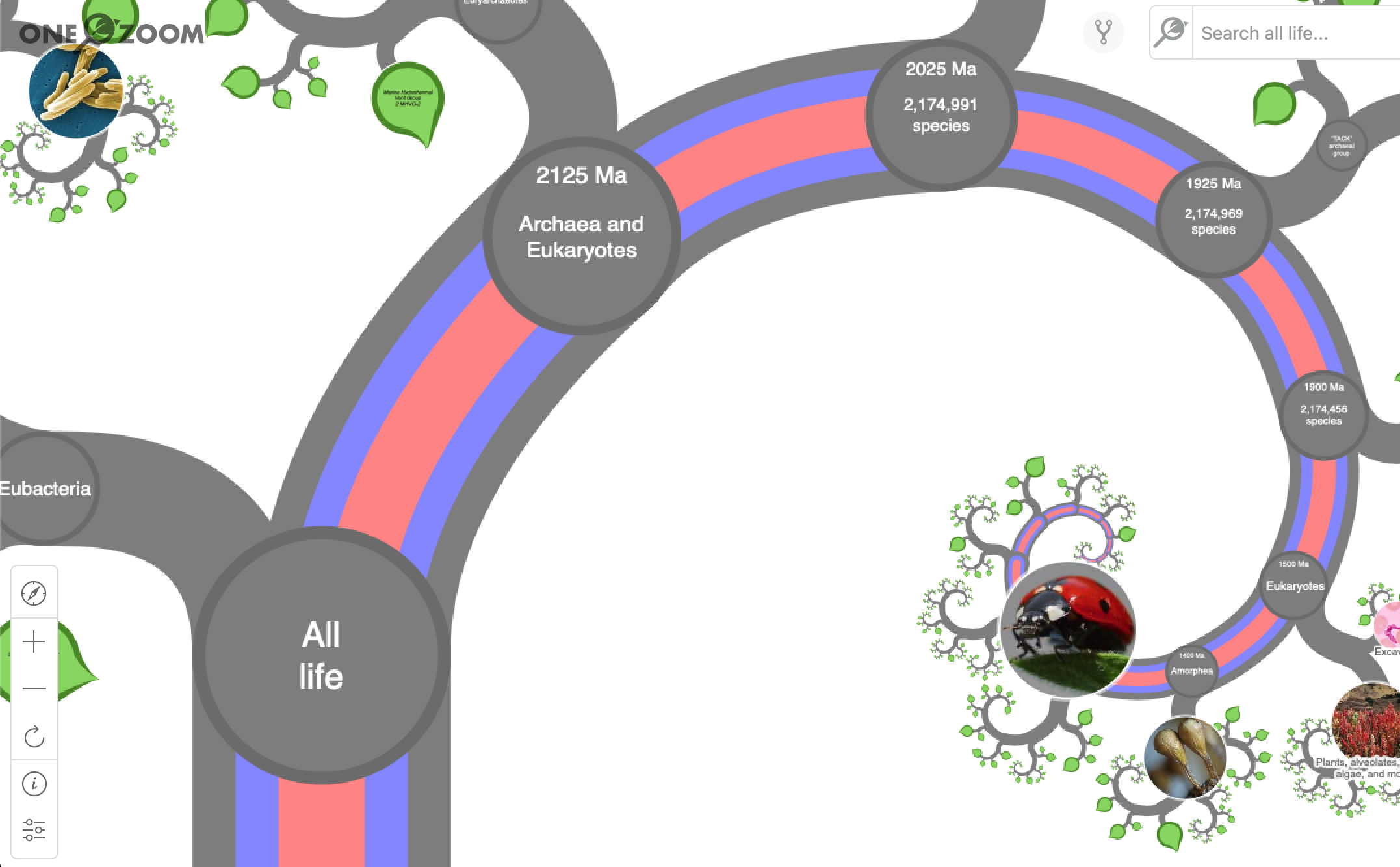

This closer view reveals the earliest divisions in the tree.

Roughly two billion years ago, all of life was composed of three groups: Bacteria, Archaea and Eukaryotes.

Bacteria and Archaea are still with us, evolving in the present, but our lineage as animals followed the path of the Eukaryotes.

The evolution of the Eukaryotic cell is perhaps the single most important event in evolutionary history.

The Eukaryotic cell, with its walled nucleus, became the fundamental building block of what we primarily perceive as life: organisms.

From plants to worms to elephants to us, the myriad combinations of Eukaryotic cells is what makes life the thing we know it as!

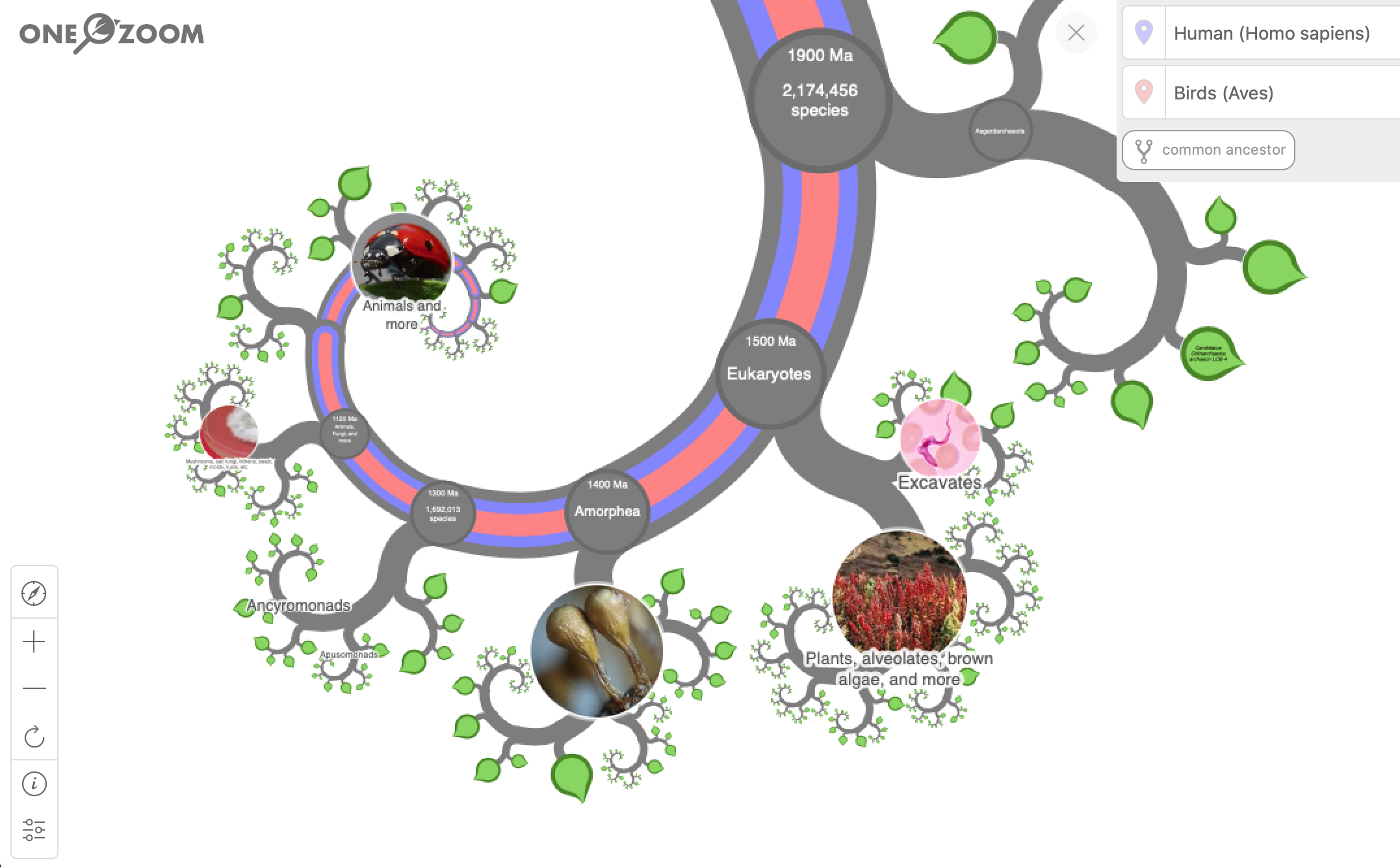

A billion years later we see Sponges diverging on their path.

Further along, we see the emergence of Bilaterally Symmetrical Animals.

That's beginning to sound like us!

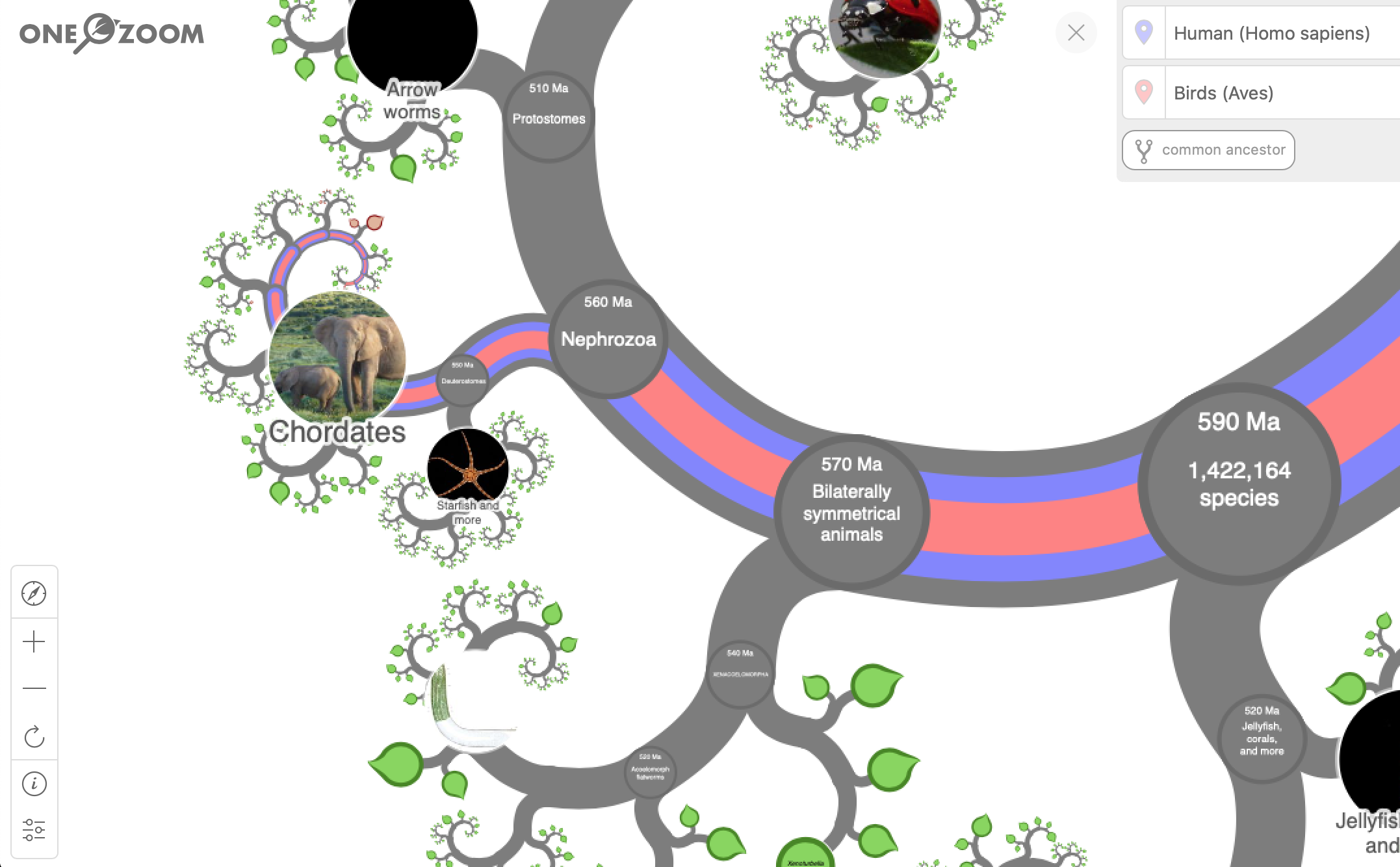

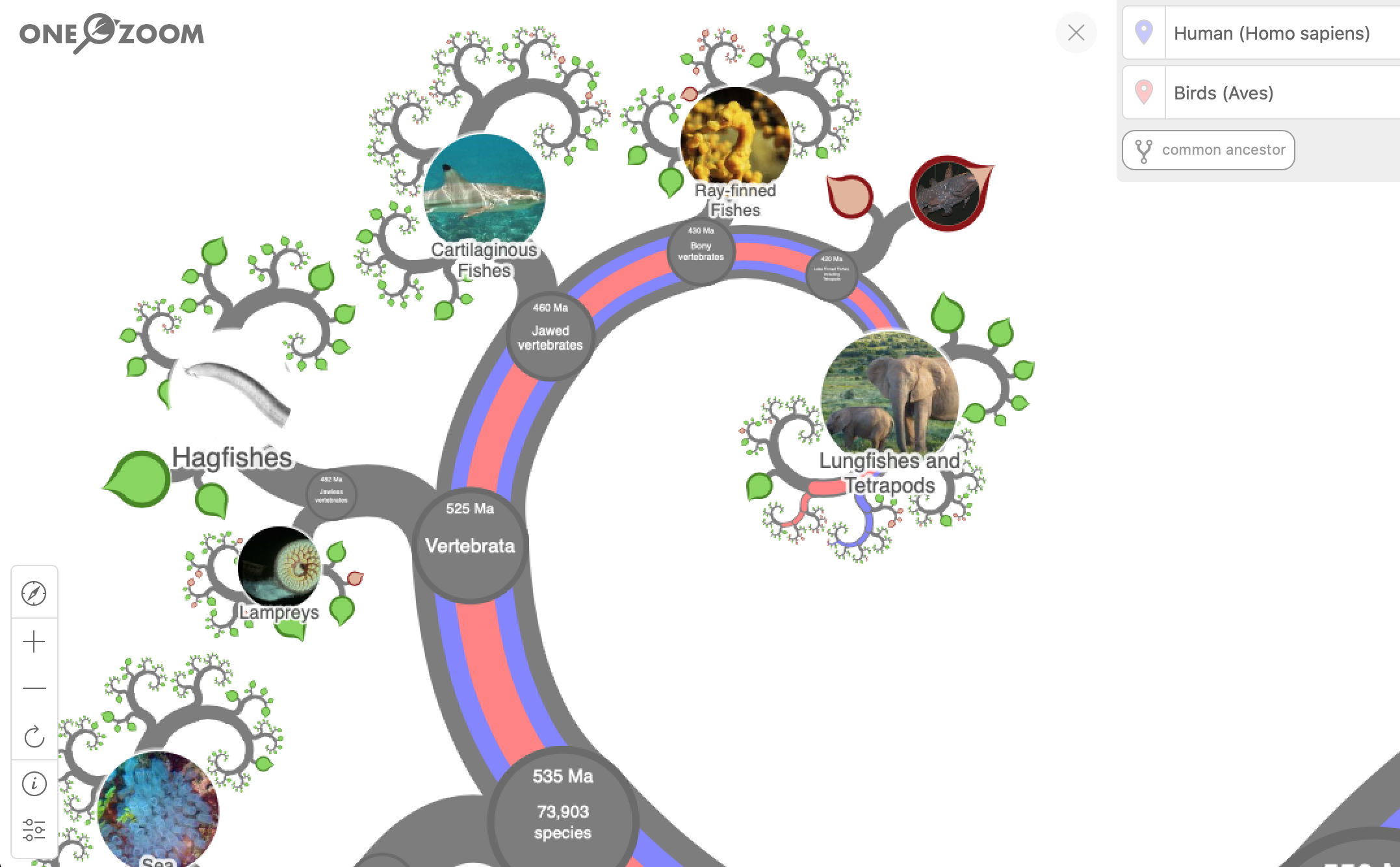

Eventually, our traces lead us to the Chordates.

We're working up to a backbone!

Another 50 million years: Vertebrates and Jawed Vertebrates.

By 320 Million years ago we and the birds both have a "modern" amniotic egg.

But at that point our paths diverge: we go down our separate path to becoming mammals and the birds follow their evolutionary path through the reptiles and lizards.

So 320 Million Years Ago, the bird lineage and our own lineage shared a common ancestor: our great-great-great-great......great-grandparent**. We are literally cousins.

**Dawkins and Wong, in their seminal book, The Ancestor's Tale estimate this as our "170-million-greats-grandparent" which would have "looked superficially like some sort of lizard".

If this material is new to you, the following two books may be of interest:

Dawkins, Richard, Wong, Yan. The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Evolution. (Great Britain: Mariner Books, 2016)

Shubin, Neil. Your Inner Fish: A Journey into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body (USA: Vintage, 2009)

What does this have to do with conserving birds?

"Us" versus "Us and them": In our everyday lives, we humans take all kinds of actions and make all kinds of decisions that affect the lives of birds. Whether consciously or not, how we use the land and how we use resources has a dramatic effect on both species and habitat diversity.

We are habitually inclined to see ourselves as both apart from and above nature. You often read "humans and animals" when the reality is "humans and other animals" or more directly, "animals".

Living things exist only within an interconnected web of life. Understanding our place in that web can help bring consciousness to our actions and decisions.

Species Diversity: Claims about one species or one family or one lineage being "more evolved" than another are not supported by evolution. Things are "differently" evolved because of the unique demands of each path. Judging the relative value of one evolutionary path to another is not possible because we do not know the future.

This idea is reflected in the well-established "Keystone Species" concept. Every habitat/ecosystem involves a complex web of life that shapes the flow of energy within that system. The removal of one species from the system may make little difference, while the removal of some other single species results in the collapse of the whole system.

In a rapidly changing environment, protecting species diversity is a way of keeping options open; of maintaining resiliency.

Earlier, it was noted that the "wetlands species" Red-winged Blackbird might be seen as an iconic bird of the Rio Fernando Wetlands. Its "buuuRRIIIIIIIIIIIIto" song is seldom absent in the breeding season.

Perhaps just as iconic, but under appreciated is another wetlands specialist the Virginia Rail. This secretive bird's subtle "kiddick kiddick kiddick" call is common in the spring, but often goes unnoticed.

Photo by Bob Friedrichs

Photo by Bob Friedrichs

This species was chosen for this example because it is present, but not often seen.

We notice the birds and trees and schrubs and maybe the turtles and frogs, but there is vast understory and underwater array of other species that support life in the wetlands.

The following list of foods eaten by the Virginia Rail provides a reminder of how much of nature lies unseen below the surface:

In the breeding season (when the Virginia Rail is at RFW), its primary foods are small aquatic invertebrates, beetles, snails, spiders, true bugs, and diptera (Fly) larvae.

Additionally, it consumes slugs, small fish, caterpillars, flies, earthworms, amphipods (small crustaceans), crayfish, frogs, small snakes, dragonfly and damselfly nymphs, ants, grasshoppers, crickets and a variety of aquatic plants and seeds of emergent plants.

Community: No living thing exists in isolation. A bird's habitat consists of a complex community of living things: plants; animals (from the smallest insects to larger mammals); bacteria; archaea.

Energy, mostly in the form of nutrients, is circulated and re-circulated among the community members, with each playing a role in the health of the system.

Habitat, Ecosystem and Biome are used to describe larger and larger communities of species, but the reality of the complex interdependent community operates at all scales. There are global flows of energy and local flows of energy. They are not independent.

Human land-use affects the flow of energy within and between these communities at all scales. Human created borders, whether between individual properties, towns, counties or countries, affect the flow of energy and can have dramatic effects on species and habitat diversity.

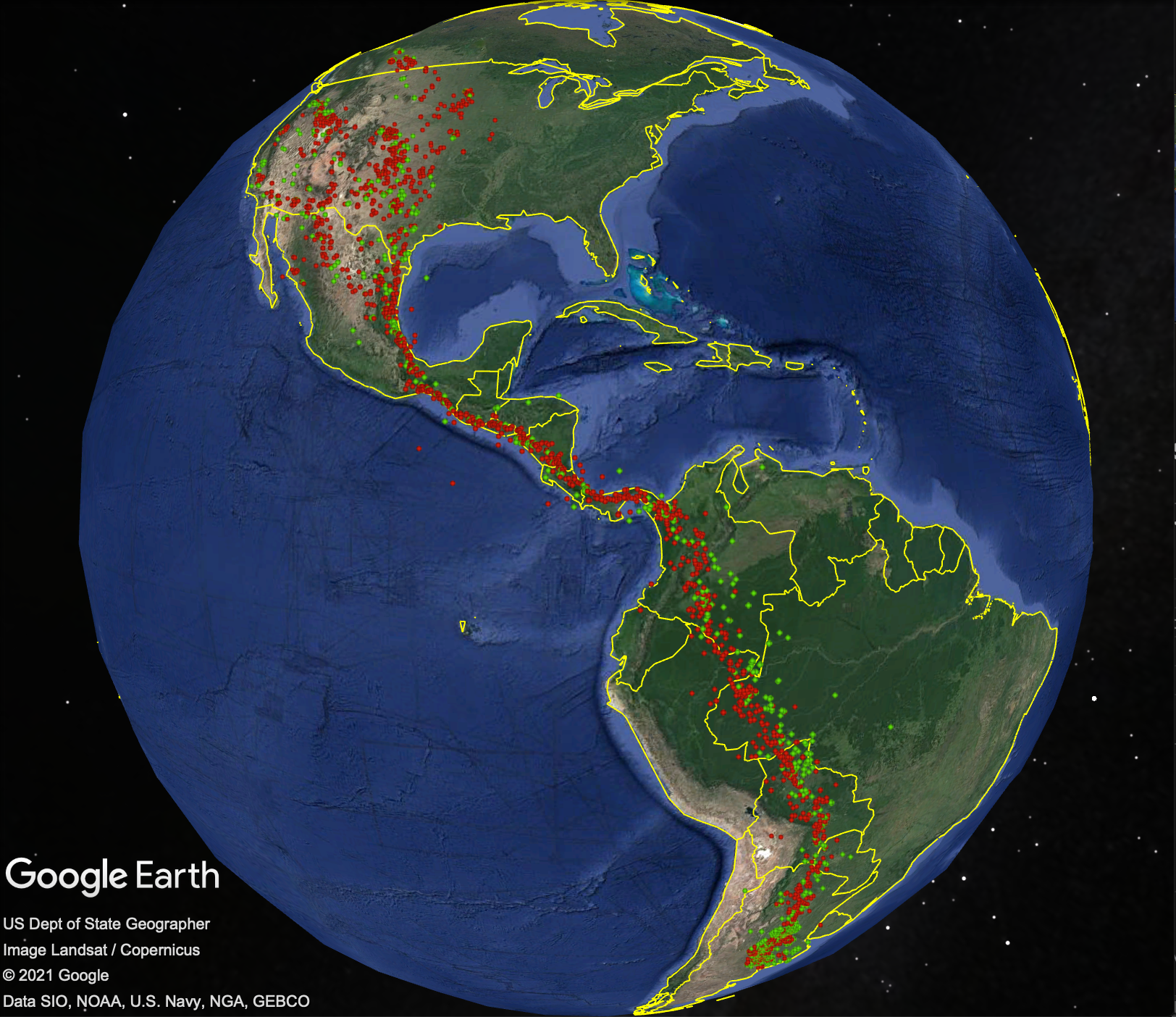

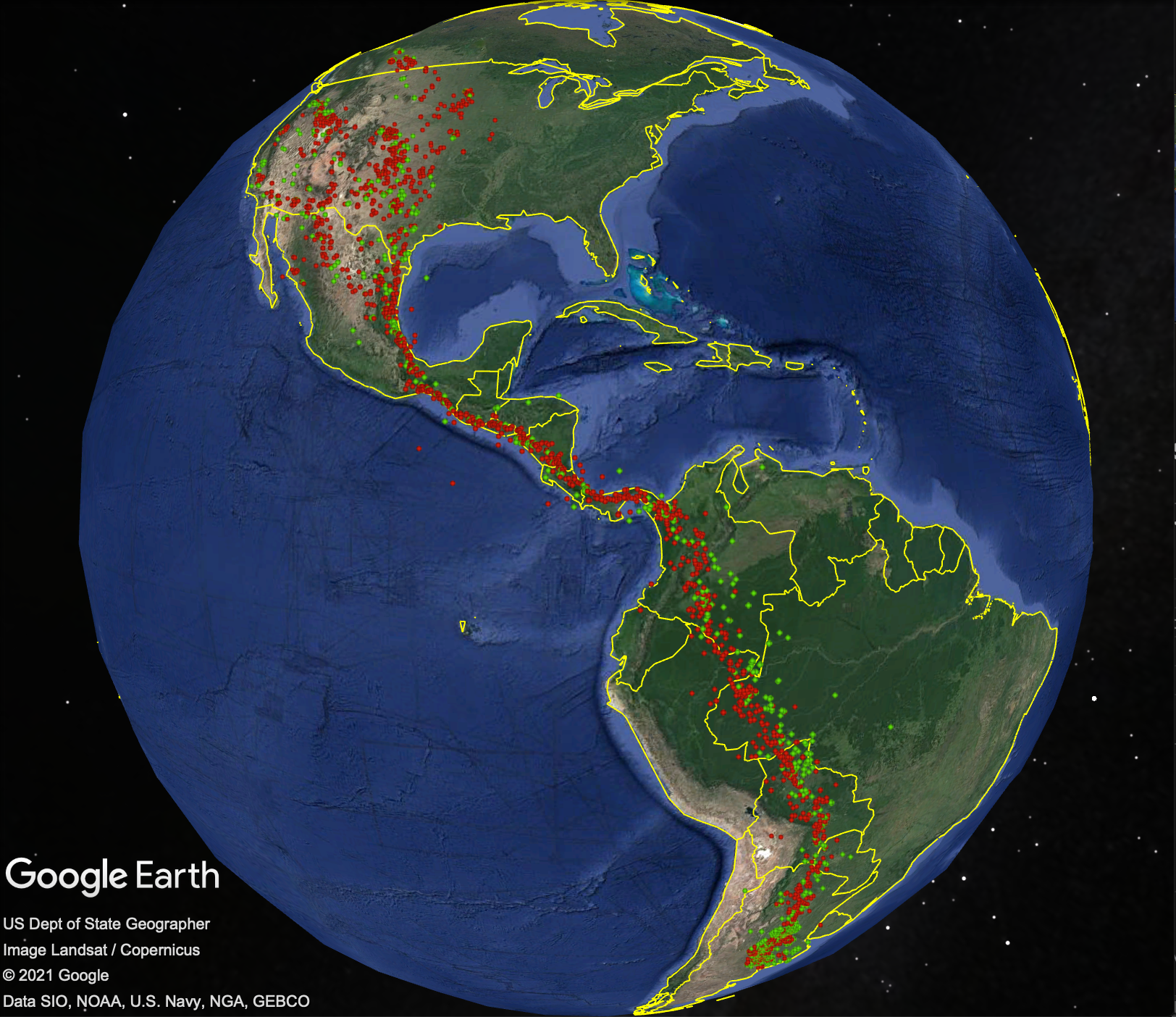

Swainson's Hawk is a Migrant Summer Breeder in the Taos area. In 2020, a pair nested in the RFW Corridor. It was selected for this example of connectivity because it has the longest migration path of all of the RFW species.

44 Swainson's Hawks were Radio-tagged and tracked by satellite in 1995-1998.

Each dot on the map is the location of one of those hawks at some point in time. The 44 hawks yielded 4515 separate locations:

- Green points: January to June (Northward migration).

- Red points: July to December (Southward migration).

These migrants travel through 15 countries, each with its own land use needs and differing levels of protection for migrating birds.

The hawks' need for forested roosting sites and locations for feeding compete with local economic pressures which often favor agricultural mono-cropping and urban development.

There is an international collaboration among conservation organizations through out the migratory path that seeks to recover and maintain the biological continuity that makes the migration possible.

While the range of the majority of migrants seen at RFW is limited to Canada, the U.S., Mexico and Central America, the same connectivity needs are present.

Data Source: Fuller, M.R., Seegar, W.S., Schueck, L.S., 1998. Routes and Travel Rates of Migrating Peregrine Falcons Falco peregrinus and Swainson's Hawks Buteo swainsoni in the Western Hemisphere. Journal of Avian Biology 29:433-440.[Data downloaded from MoveBank.org - 2017]

Whether talking about Habitat, Ecosystem or Biome, the primary source of energy for the community of species is solar. It is made available in the form of photo-synthesized plant material.

Some members of the community depend on live plant material. Others depend on dead plant material. As community members consume other community members, energy moves up the food chains powering the health of the whole community.

Native plants have a special role in each community. The members of the community (plants, animals and microbes) share an evolutionary history. The characteristics of all members of the community have been shaped by their relationship to each other.

The introduction of non-native plants or animals changes the evolutionary pressures on all members. In general, it results in the reduction of the carrying capacity of the system.

Solar Radiation, Adapted from: Lamb, H. H. 1972. Climate: present, past and future. Vol. 1. (Methuen)

Values are Daily Totals of Solar Energy available ignoring atmosphere.

Units: g cal/cm^2

This graph shows the distribution of solar energy as it encounters the Earth's atmosphere.

Latitude is shown on the vertical axis. Months of the year on the horizontal.

The levels for our northern summers are in the upper left part. The levels for the southern hemisphere summer are in the lower right.

Levels at the Equator are high throughout the year. The levels of the southern winter exceed those of the northern winter since the Earth is farther from the sun during the northern winter.

Here, the locations of the Swainson's Hawks from the Habitat Diversity and Connectivity example are plotted on the graph by latitude and date. (The absence of data in June has to do with technical issues, not an absence of hawks.)

As you can see, the hawk migration essentially tracks the changing north-south position of the sun in the sky.

The Swainson's Hawk's preferred breeding habitat is native grasses on the plains of North America. Grasshoppers are included in their diet.

In winter, on the plains in Argentina, grasshoppers make up the bulk of their diet as they forage in grasslands, plowed fields and pasture lands.

Here is a map of the principal watersheds of the Taos Valley.

The Rio Fernando watershed is outlined in red.

Rio Fernando Wetlands (RFW) is shown near the downstream end of the watershed.

From its headwaters at 10,000 feet, to its confluence with the Rio del Pueblo it connects many diverse habitats. Bird species that are not seen or rarely seen at RFW, can be found at locations higher up in the watershed.

A critical organism in most watersheds is the Beaver. Among other things, the work of beavers increases the amount of water available for plant production, increases biodiversity and sequesters carbon. In reality, most of land we live on and farm was to some extent created or shaped by beavers.

Like most streams in Northern New Mexico, the Rio Fernando is heavily affected by human land use: highways, roads, home and business development, septic systems, fencing, noise, among others, pose significant threats to the diversity and health of the biological community that has evolved there.

All of this makes it difficult for beavers to perform their wonders on the watershed. However, there is a strong movement across the country to make it possible for beavers and humans to co-exist. Here is a link to the 2020 New Mexico Beaver Summit recordings. Beavers are being encouraged in many different situations. Practical methods exist to address the beaver-human conflicts.

The mix of private and public lands and the array of City, County, State and Federal entities involved pose a set of challenges to conservation of the watershed.

Two clear paths for positive action emerge:

- Action you can take on your land.

- Collaboration for all else.

The opposite of connectivity within a biological community (at any scale) is often referred to as "fragmentation". It usually involves the destruction or degradation of some part of the biota of the community. It may partially disrupt the connectivity or it may leave a segment isolated.

Resultant decreases in diversity and reproductive success follow.

The way much land-use is organized around individual-private-property-plots easily lends itself to habitat fragmentation. On the other hand, you have a great deal of control within the confines of your own land or yard.

One Approach:The kinds of fences you erect, the choices between hardscape and vegetation, or between mono-crop lawn and diverse native plantings, can have a dramatic effect on the bird life around you. At a neighborhood scale, the effects could be amplified.

The production of plant material is at the base of habitat health and species diversity. When thinking about one's property, it is useful to contemplate the extremes of a paved parking lot and a diverse array of native plants.

The idea of biologically conscious personal land-use has been formalized into the concept of the "Homegrown National Park" by noted biologist and author David Tallamy in his book: Nature's Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation That Starts in Your Yard. Read a Review of Tallamy's book on the Virginia Native Plant Society website.

Two Resources at Audubon.org on making your yard/land bird-friendly:- "How to Make Your Yard Bird Friendly"

- Search for Native Plants by Zip-Code. (Note: You do not have to enter your email to see list.)

The economic pressures to develop open land are formidable. There have been massive changes in land use in the Taos valley over the past 50 years. While there is still a good deal of open land in the Taos Valley, any property is just one sale away from dramatic changes in its ability to support local biodiversity.

A Conservation Easement on your private property is a way to ensure that the property will retain its current character into the future. The Taos Land Trust has the expertise to help you in this endeavor.

Here is a link to a TLT publication that outlines the benefits of establishing an easement as well as the process involved: Taos Land Trust: Landowner's Guide

Contact the TLT for more information: 575-751-3138

Restoring, enhancing and protecting bird habitat across the Taos Valley requires collaboration.

Here is a list of organizations that can help you in your efforts and can benefit from your continued support and input: