- List of Species Observed in RioEmbudoBirds.org area (Updated 2023):

- All Seasons, All Species

- Species Present All Year

- Winter Visitors

- Spring-Fall Transients

- Migrant Summer Breeders

- Non-breeding Vagrants

- Observing Birds

- Local Bird Counts

- Bird Migration

- Bird Song and Sound

April 25, 2013:

Conexiones: La Junta del Río Pecos y el Río Grande, Northern New Mexico: Mountains. Mesas y llanos. Rivers. Acequias. Features which create a sustaining sense of place. There are many rivers in New Mexico, both short and long. Our own Río Embudo is only a dozen miles old when it empties into the Río Grande. If you follow its source back to La Jicarita you add another twenty miles or so. Once the Embudo waters join the waters of the Río Grande, the long journey begins. Sweeping down the central valley of New Mexico until it forms the border between Texas and Mexico, it traces out nearly 1,900 miles from its source in Colorado a su boca en el Golfo de México. For birds, The Río Grande and its sister to the east, the Río Pecos provide a migration pathway from Mexico north. Migrants from Central America and Mexico traverse one or the other of these rivers as they make their way to breeding grounds further north.  Female Western Tanager El Bosque 2011  Male Western Tanager El Bosque 2011 Hundreds of thousands of songbirds like these Western Tanagers depend on the riparian and irrigated acreages along the two rivers twice each year: moving north in the Spring and south in the Fall. Many of us have visited the headwaters of the Río Grande in southern Colorado. We know how the Río Chama swells and muddies the Río Grande during rains. Many of us have some idea of how the Río Pecos joins with the Río Gallinas as it begins its journey south. But where do these rivers end?

Where the Pecos ends: Del Río, Texas lies on the east bank of the Río Grande nearly 300 miles north of the Gulf (See Map). Its Mexican counterpart, Ciudad Acuña, lies on the west bank. About 35 miles north of Del Río and Ciudad Acuña, the Río Pecos flows into the Río Grande. At la boca del Río Pecos, the river flows out of a gorge which is more than 10 miles in length. At la junta (the confluence) with the Río Grande, the gorge is more than 800 feet wide with stone walls more than 250 feet high. In the photo below, the Pecos is flowing in from right to left (East to West). When you enlarge the photo, you will be able to see the Río Grande flowing North to South. (Follow the colors down at the base of the far wall of the Río Grande cañon: White, Red, Green, the waters of the river.) |

|

Where the Río Grande ends: The Río Grande flows into the Gulf of Mexico at Boca Chica Beach about 20 miles east of Brownsville, Texas and Matamoros, Mexico. In the photo below, the Gulf is on the left, Mexico is on the far shore (with Light House) and the U.S. is on the right. Click here to see Maps and more Photos of la Boca del Río Grande and photos of banded Red Knot (Calidris canutus) encountered there. |

|

Black-bellied Whistling-ducks: You cannot visit the Rio Grande in south Texas without visiting the border fence. It cuts through neighborhoods in Brownsville and other Texas towns. It interrupts animal trails that have existed for millennia. To visit the Sabal Palm Audubon Center and Sanctuary one must get to the other side of the border fence. The Sanctuary is in the U.S., but like most of the U.S. bank of the Río Grande and many neighborhoods all along the border, it is outside of the fence. This first picture is of an agricultural field on the U.S. side of the fence. The fence borders the southwest edge of the field.  Agricutural Field bordered by Border Fence Brownsville, Texas

Here is a closer view of the same field:  Agricutural Field bordered by Border Fence Brownsville, Texas

The previous pictures were taken from the road pictured below. Straight ahead is an opening in the border fence which leads to the wildlife sanctuary.  Access to Sabal PalmSabal Palm Audubon Center and Sanctuary Brownsville, Texas

At the opening looking north:  Fence opening looking north. Brownsville, Texas

Looking south:  Fence opening looking south. Brownsville, Texas

I visited 3 major wildlife refuges that required passing through the border fence. Whatever one's plitical views might be, seeing the fence in person is likely to cause you contemplate the many issues that surround its construction. From an ecological standpoint, the wall disrupts long established patterns of movement for all the area's animal species, including Homo sapiens. People often think of the Río Grande as something that separates us from something else: the U.S. on one side and México on the other. But in reality, the river is something that connects us. From a bird migration perspective, the Río Grande and el Río Pecos y el Río Colorado provide food-rich super-pathways used by millions of migrating animals. Human travel along those pathways has existed for millennia. The border fence represents a new era in those relationships. The fence commands your attention as you pass through it. I may have come there to be in nature, but I am not going to get to my destination without some contemplation of this seemingly most unnatural construction. .......but then I leave the fence behind and in a few minutes I am lost in the beauty of some of the last remaining Sabal Palm forest in North America:  Sabal Palms Sabal Palm Audubon Center and Sanctuary Brownsville, Texas

Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides)  Spanish Moss Sabal Palm Audubon Center and Sanctuary Brownsville, Texas

That's why I try to get outside into nature whenever I can. One encounter with one species is enough to bring me back into a warm connection with the natural world: that web of life from which I came and to which my fate is tied. Brother and sister Black-bellied Whistling-Duck (Dendrocygna autumnalis) standing on top of a broken Sabal Palm.  Black-bellied Whistling-Ducks Sabal Palm Audubon Center and Sanctuary Brownsville, Texas

Black-bellied Whistling-Ducks Sabal Palm Audubon Center and Sanctuary Brownsville, Texas |

April 20, 2013:Spring Migration Texas/NM, April 5-19, 2013 Travel = change of location = change of habitat = change of species. Altitude Change: You don't have to travel far to see the effects of changing habitat on species observed. In New Mexico, a short drive can result in a dramatic change in altitude. If you are here in Dixon at about 6,000 feet, it is common to see the Western Scrub-Jay. A bird of Piñon-Juniper woodland, it is commonly seen in adjacent irrigated lands.  Western Scrub-Jay Arroyo de la Mina, September 23, 2006 If you travel a short distance to higher elevations, you will eventually stop seeing the Scrub-jay. There will still be an ecological niche for a jay, but the jay you will see is the Steller's Jay. During a 2013 Spring Migration Count in Taos County, only Scrub-jays were seen below 7,000 feet in altitude. There was a transition zone around 7,300 feet where both Scrub-jays and Stellar's were observed, but above 7,500 feet only Stellar's were observed. See Data from the Count In the winter, it is also possible to see the Stellar's Jay in the Dixon area. On this year's Dixon Christmas Bird Count, three individuals were seen: one each in Velarde, Embudo and Apodaca. But the rest of the year you will have to get up in the mountains. See Dixon Count Results. So, what if you drive east? You will experience another transition to a different species of jay. But this transition takes some time. Once you get on the east side of the Sangre de Cristo range, you will continue to see Western Scrub-jays, but you will also start to encounter its eastern counterpart, the Blue Jay. You will continue to get a mix of Scrub and Blue jays until you reach western Oklahoma or East-central Texas. After that, it is Blue Jays all the way to the east coast. I have seen a Blue Jay in Dixon one time. It was in my front yard in the spring about 10 years ago. That is one occurrence since I started paying attention about 15 years ago! Does this kind of "species replacement" happen with other groups of birds? It happens in all families of birds. In general, the transition from western species to eastern species happens along a line running north-south through Oklahoma City and Dallas, though it veers a little west as you get further north. This line falls along the western edge of the eastern forest. Driving I-40 across Oklahoma, it is easy to observe the transition. [Just about 3 degrees west of that line lies the 100th Meridian (100 degrees west), which is an important dividing line between the arid west and the wetter east.] On a trip last Spring to Texas to greet returning migrants, I witnessed such a transition in the Flycatcher family. Flycatcher "replacement": A flycatcher common in Dixon during the summer is the Cassin's Kingbird. Another Kingbird, the Western Kingbird, is seen in Embudo and Velarde, but is not as common as the Cassin's.  Cassin's Kingbird El Bosque, 2007 Driving out of Dixon on April 5th, I had not seen either yet, because they don't arrive here until the last half of April. Had I departed on May 5th, there would have been Cassin's Kingbirds all over Dixon and Embudo and a few Westerns as well.  Western Kingbird Bosque del Apache, 2007 By the time I was in central Texas, I was seeing the eastern counterpart of the Cassin's and Western, the Eastern Kingbird. I was also seeing a few migrating Westerns, but in southeast Texas I saw only one Western, while the Eastern became an almost constant presence.  Eastern Kingbird Texas Gulf Coast, April 11, 2013 Another Flycatcher: In eastern New Mexico, we began to encounter one of my favorite flycatchers, the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher. This is another bird that you will need to go east to see regularly. But not too far east. This species has an interesting range. During the summer, it breeds to the east of us, but only as far east as Lousiana, Arkansas and Missouri. But come the Fall, this species heads south to its wintering grounds in southern Mexico and Central America. On the map, the Summer breeding range is shown in the dark orange. The wintering grounds are shown in blue with the migration path between them in yellow. All individuals in the species traverse this migratory path twice a year, moving north in Spring and south in the Fall. I have seen hundreds of small flocks (10-20 individuals/flock) during the Fall migration in Veracruz, Mexico. No matter how many times I see this bird, it is a beauty every time! One last "replacement": Everyone here is familiar with the Turkey Vulture. A "kettle" of Turkey Vultures rising on a thermal at 9 or 10 in the morning is a common sight in Dixon. The photo on the right shows one soaring over the Río Grande near the Taos County Line. I never stopped seeing this species on the trip to Texas, but soon after leaving New Mexico, observations of another vulture, the Black Vulture (pictured on left) became daily occurrences. So in reality, this was not a "replacement", but an addition. I moved out of an area with Turkey Vultures only, into an area with both vultures present.  Black Vulture Texas, April 12, 2013  Turkey Vulture Río Grande, July 15, 2012 The two vultures are easy to distinguish from each other. Differences in wing shape, apparent length of the tail and placement of white on the wings are very apparent. There are differences in wingbeats between the two species that allow long-distance identification even when the shape and plumage are not discernible. The quicker wingbeats of the Black Vulture allows an observer to readily pick it out of a mixed flock at a great distance. See a video showing other Turkey Vulture identification features. Click here and scroll down. Water versus no water: Four Species There are some species of birds that are found only where there is abundant water. Here I share some favorite photos from the Texas trip of four such species: Great Egret, Snowy Egret, Green Heron and Roseate Spoonbill. All have been recorded in New Mexico. Great and Snowy Egret can be found up and down the the Río Grande and the Río Pecos. While they are both common breeders at the Bosque del Apache, they are generally more rare in other locations. The Green Heron is also a common breeder at the Bosque and a migrant along the Ríos Grande and Pecos. I have observed this species at an oxbow pond along the Río Grande near Cachanillas, just south of Velarde. There are only a handful of Roseate Spoonbill records in New Mexico. Your chances of seeing one here is close to zero. For all of these species, the density of individuals is much, much higher along the Gulf Coast of Texas. The accompanying photos were taken at two locations: A rookery, or breeding colony at High Island, Texas and the nearby Anahuac National Wildlife Refuge. I was captivated by the sheer beauty of these birds. It was overcast the whole day these were taken, so the light was not great, but even the poor lighting cannot hide the beauty of these natural wonders!. |

April 2, 2013:Spring Migration 2013: Update April 2 Sounds of Migration: There are two sounds that mark the beginning of the spring migration: the sharp two-note call of the Black Phoebe and the slow, plaintive, downward slurred "pee-ee" or "pee-eer" of the Say's Phoebe. I heard a single Say's Phoebe call from the parking lot of the Dixon Cooperative Market on March 8th. By March 15th, I was hearing it consistently in locations all around the Embudo area. Walking now along the Río Embudo or the Río Grande you are sure to hear and see the Black Phoebe. Here is a video of the Say's Phoebe making its "Pee-eer" call. The "drink, drink, drink, tea....." of a Spotted Towhee is heard in the background. This Phoebe was high in a Cottonwood, but Say's Phoebes are much more likely to seen calling from low perches like fence posts or Mullen stalks. Migrating Swifts: I generally see a few White-throated Swift during the spring migration. I saw many this year. The first sighting was a group of 7 individuals on March 18,  White-throated Swift El Bosque, March 23, 2013 On the 20th, I saw 3 individuals, but in the late afternoon of the 21st, group after group moved NW along the valley.  Violet-green Swallow Silhouette Sometimes, people "under-identify" swifts as Swallows. A silhouette of a swallow appears to the right. The leading wing edge is curved. The trailing wing edge is flat. The wings of a swift are curved on both the leading and trailing edges. This is clearly shown in the March 23rd White-throated Swift photo. It shows the swift's diagnostic "sabre-wing" shape.  White-throated Swift March 25, 2013 Because of the angle of the bird in the second swift photo, the wing shape is less pronounced. From this photo, it is easy to see how one might momentarily mistake a swift for a Violet-green Swallow. However, a Violet-green Swallow would show white below, from the bill all the way to its short, dark tail. Arrival of the Turkey Vultures: The spring return of the Turkey Vultures is an event noticed by lots of people. They begin arriving in late March, with most of them here by April 1st. Generally, there are about 20 individuals that roost in Dixon, though twenty years ago the number was consistently around 40. In the range map shown below, the purple area is the year-round range. The orange area represents additional areas the vultures return to for summer breeding. There are five sub-species of Turkey Vulture. One of those sub-species is a long-distance migrant, spending its winters in South America. The known populations of this sub-species are in the west. It is possible that our local vultures are among these long-distance migrants. The only way to know for sure would be to capture and radio-tag some of them. An extensive radio-tag study is underway now at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania. To see maps of radio-tagged Turkey Vultures, visit the Turkey Vulture Migration Project Website. It is difficult to separate the subspecies in the field, so it is likely that where our Turkey Vultures spend their winters, whether in South America, Central America, Mexico or in the south of the U.S., may remain an unanswered question.

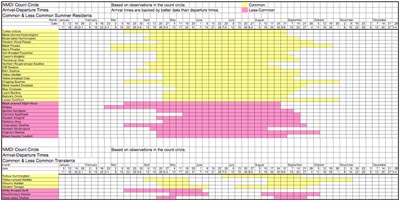

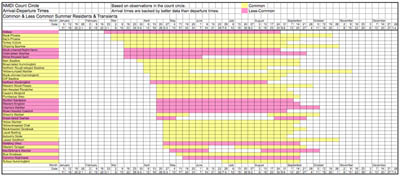

The following is a list of 2013 counts at the Dixon roost: Here are two video clips showing the critical identification features of the Turkey Vulture. The first shows the bi-color wing. The second shows the wings held up at an angle (dihedral) and the rocking motion as the vulture glides. The dihedral configuration and the rocking motion taken together are diagnostic in Turkey Vulture identification. Who Is Arriving, When? I have been paying close attention to the presence of bird species in the Embudo area for more than 15 years. I have pulled together all of my records and consulted other sources such as records from eBird to come up with some preliminary "first" and "last" dates for the summer residents and transient species. The screen-shots below are from two downloadable PDFs. (Click to display in the browser, right click to download.) Both files show arrival and departure information for the Common and Less Common species in our area. The first file shows the approximate time period that each species is present in the Embudo area. The second file is the same information, but ordered by the arrival date for each species. The arrival dates presented come from actual observations of the species during the time period shown. However, some of the dates are a result of only a few observations. I would be very interested in hearing about any observations earlier than the arrival dates given. Though not depicted in the graph, the peak of the migration season is around the 2nd week of May. Two Last Thoughts: 1. An observation technique that works during the migration seasons is to focus your binoculars on a distant mesa top or on low clouds and then just slowly scan from horizon to horizon. Then move your orientation over a few degrees and repeat. Most times of the year, this technique will not be very productive, but at this time of year there are birds moving through much of the time and some are high, just on the edge of visibility with binoculars. It won't work every time, but you may be surprised what you find. 2. For me, the Spring migration is a joyful time of re-connection with "old friends". As I hear or see each species for the first time, I experience something similar to what one might feel about "going home" or "coming back to oneself". It feels settling and quieting. I suppose it also serves as a comfort in as much as we seem to have once again, at least for this year, escaped Rachel Carson's "silent spring". |

March 3, 2013: Black-capped Chickadee in El Bosque April 22, 2011 Spring Migration 2013 Begins The signs of spring are everywhere. On warm days, the Black-capped Chickadees are singing their two note "fee-bee" whistle. This song, sung primarily by males, is used for marking territories and attracting mates.1 Black-capped Chickadee's "Fee-bee" Song recorded near Río Embudo, January, 2008: I have seen both Black-billed Magpie and American Crow carrying nesting materials. You may have noticed more extensive House Finch song and the presence of an upward sliding whistle at the end.  Pale female Robin on Río Grande With spring comes the northward migration of birds. One sure sign of the migration is the flocking of American Robins. Last evening, there were at least 150 Robins in the trees and fields around the bridge in El Bosque. We have Robins here all year. They breed here in the summer. But in the winter, the number of Robins increases as birds from further north in the U.S. and Canada move south searching for fruit to eat. Large numbers winter in the southern U.S. and northern Mexico. They begin their northward migration as soils thaw, allowing access to invertebrates such as earthworms.2 On March 21, 2011 I was counting birds along the Río Santa Fe near Cieneguilla. There were large flocks of Robins all over the place. I wrote down the number 550. That was a conservative estimate. There were large groups circling all around and then some moving off to the north.  Black Phoebe in Cachanillas Two of the first migrants to arrive in the spring in the Embudo Valley are the Black Phoebe and the Say's Phoebe. These are both common summer breeders all over northern New Mexico. It is not surprising that they are the first migrants to appear here as a few individuals over-winter as far north as Velarde. The Black has been recorded in 9 of the 16 years of the Dixon Christmas Bird Count. The Say's has been recorded in 5 of the years. These sightings were all in Velarde.  Say's Phoebe in Rinconada Both species are usually in the Embudo Valley by the second week in March. Look for the Black Phoebe making its sharp two-note call right at the river's edge, often on a low branch right over the water. You will find the Say's Phoebe sitting on fence posts or wires in the agricultural fields. If you listen closely you can hear its slow, plaintive, downward slurred "pee-ee". Notes: 2. Sallabanks, Rex and Frances C. James. 1999. American Robin (Turdus migratorius), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/462 doi:10.2173/bna.462 |

January 17, 2013:

Immature Bald Eagles Everyone recognizes the adult Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus). Its white head and white tail contrasting with its dark body leaves no doubt what species you're seeing. But people who are not familiar with immature eagles are often surprised to discover a very different-looking bird. Sarah's photo at the left shows an adult in the upper left corner and an immature in the lower right. (Click Photo to Enlarge.) She described her sighting this way: "What an experience it was to watch the eagles today. When I first noticed them, I happened to look up and see 3 eagles: 2 adults and the 1 juvenile. One of the adults flew up the river while the other 2 stayed together for quite awhile. Eventually the other adult took off down the river leaving the juvenile behind. The juvenile stayed around for several more minutes soaring right over us (Mom and me by this time). So graceful." As the young eagle continued to soar, Sarah took more photos: Here is a closeup of the young bird. Immature Bald Eagles show lots of white under their wings. A first year bird's head, breast and belly are dark, with white in the wings. Second and third year birds (which this one is) show extensive white on the body.(Note: The highly contrasting white breast is due to sunlight. See next photo.)  Photo: Sarah Nelson A Bald Eagle does not obtain its adult plumage until it is about 5 years old. Each summer, the birds feathers are replaced by new ones (molting). By the fourth or fifth year, the yearly molt results in the well known adult plumage. Notice the feathers at the tip of the right wing (up in the photos). The fourth feather from the front is broken. By mid-summer, that broken feather will be replaced by a new one.  Photo: Sarah Nelson Bald Eagles are commonly seen along the Río Grande and occasionally on the Río Embudo. Enjoy them now! By March, the eagles will begin their migration to the north to their summer breeding areas with some going as far as northern Alaska. (Click to see Range Map) They won't return to the Embudo area again until next November. Go to Bald Eagle in "Learning the Birds of the Río Embudo" |

Dixon Christmas Bird Count: 2012

The 16th Year of the Count The 2012 Annual Dixon Christmas Bird Count was held on Saturday, December 15. Eighteen counters turned out. Counters came from Apodaca, Cañoncito, Dixon, Embudo, Rinconada, Velarde, Pilar, El Prado, Española, Los Alamos, Santa Fe and Albuquerque. The count area is a circle, 15 miles in diameter. The center of the circle is about 1.5 miles up the Arroyo la Mina. See satellite image below. Enlarge Image Each year counters are divided into 5 groups. Three groups count along the Río Grande. One counts in Velarde. Another covers La Bolsa and the Río Grande to Rinconada. The third covers Rinconada and the Río Grande to the Glen Woody Bridge. Two groups count along the Río Embudo. One from La Junta east through Dixon, the other counts Apodaca, Cañoncito and the road to Ojo Sarco. Click here for details of what birds each group saw. Some of the participants on this year's count were beginners, but every counting group, called a "party", had at least one person who was capable of identifying all the species by both sight and sound. Each party began counting at 8:00AM and were out for six to seven hours. One person in each party kept a written tally of every bird seen and heard. Eventually, the "party" lists were all combined and the totals for the whole circle were entered into a National Audubon Society CBC database. There are more than 2,000 count circles across the U.S., Canada, Mexico and Central America. The data from all of those counts is available to anyone with a computer. Scientists all over the world utilize the data in their bird research. Access CBC Data

How did this year's count compare with previous years?

The total number of individuals counted this year was 5091. That is the highest count ever. Here is a table showing the totals over the history of the count: The top row shows the actual number of individuals counted. The second row gives the sum of the hours spent counting by each of the five groups (Party-hours). The last row is calculated by dividing the number of individuals by the amount of time spent counting (Individuals / Party-hours). The amount of effort expended varies from year to year. This is affected mainly by the availability of experienced counters and whether the weather prevents safe travel to the count area. Note: In this year's count (113th), the five parties collectively put in 33.5 hours. Last year, because of poor travel conditions, there were only four groups and they put in just 21 hours. The Comparison: The effort-adjusted data is what bird researchers generally use. Here is that data for the 16 years of the Dixon count (1997-2012):

Looking at the graph above, one might conclude that 2012 had been an extremely good year for birds in the count area. However, of the 5,091 individuals counted, 1,969 of them were of one species, the European Starling. 1,662 of them were counted in Velarde. Large flocks of Starlings are often seen on the north edge of Española, sometimes creating dramatic, rapidly-changing patterns as the flock sweeps around the sky. See Video of Starling Murmurations. Before this year, the highest count for Starlings had been 583 individuals with a 15-year average of 248. Here is 16 years of Starling data from the Dixon Count:

It is unlikely that the huge increase in the local Starling population was due to breeding success in the area. After the summer breeding season, Starlings often wander as much as a couple of hundred miles from their breeding area.1 This is a more probable explanation. While the Velarde count was very high, some other count, for instance, one in southern Colorado, may have had a particularly low count. One way to gain more understanding about the situation would be to look at data from many count sites in New Mexico and Colorado. Back to the Comparison: One approach is to consider all species except European Starling. The following graph shows 16 years of data with Starling numbers removed from all years:

So "How did this year's count compare with previous years?". It was above average, but given the variation from year to year, it was in the normal range. It does not fit into some clearly discernible trend of increasing or decreasing population. It will be interesting to see what happens to the numbers if the drought continues. Dry conditions on a bird's breeding ground often leads to reduced breeding success. But studies show that a one-year drought is often not discernible in terms of population decrease. However, multi-year droughts may have substantial effects on populations.2 Another aspect is that about 20% of the species recorded on the count do not breed locally. They only pass the winter here until they can return to their breeding grounds. A later blog entry will consider only the species that breed locally. Why do people do these counts? Is it this kind of mathematical analysis that causes people to be willing to be out all day in very cold, sometimes snowny conditions to do these counts? I don't think so. Most counters realize that they are doing what is often called "Citizen Science", but most are out there because they love to be in nature. Being out on a cold, winter day from sunrise to sunset, doing nothing but paying attention to the birds has its own rewards. For me, it is has a calming effect. Most people around here know how a half-hour walk along the river can change one's perspective. Take that half-hour walk and turn it into an eight-hour walk. It changes how you feel. For more information, go to the RioEmbudoBirds Christmas Bird Count page. References: 1. Cabe, Paul R. 1993. European Starling (Sturnus vulgaris), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/048 2. George, T. Luke, Ada C. Fowler, Richard L. Knight and Lowell C McEwen, Impacts of a Severe Drought on Grassland Birds in Western North Dakota. Ecological Applications, 2(3), 1992, pp. 275-284 |

Copyright 2006-2021 by Rio Embudo Birds.org --- All rights reserved.